In 1959, DeFeo was chosen—along with Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella—for a survey show at the Museum of Modern Art called “Sixteen Americans.” But for a time after “The Rose” was lowered out the window of her Fillmore Street studio, in 1965—an event recorded in a lovely, luminous short film by her friend and fellow Bay Area avant-gardist Bruce Conner—it left a vacuum that brought DeFeo’s work almost to a standstill. She found a way forward in 1970, when she used a Nikon and a Yashica and began teaching herself how to use them. Instead of taking a photography class, she researched and picked up tips from students at the San Francisco Art Institute, where she taught, and learned from her mistakes. A show of the photographs of Man Ray, who invited accidents and exploited the distortions of the darkroom, inspired her to be “more comfortable with my approach,” she wrote to a friend at the time. “I have neither the temperament—nor the facilities—for a hard-core technical path to perfection,” she added, and proceeded to make the best of it for five busy and remarkable years.

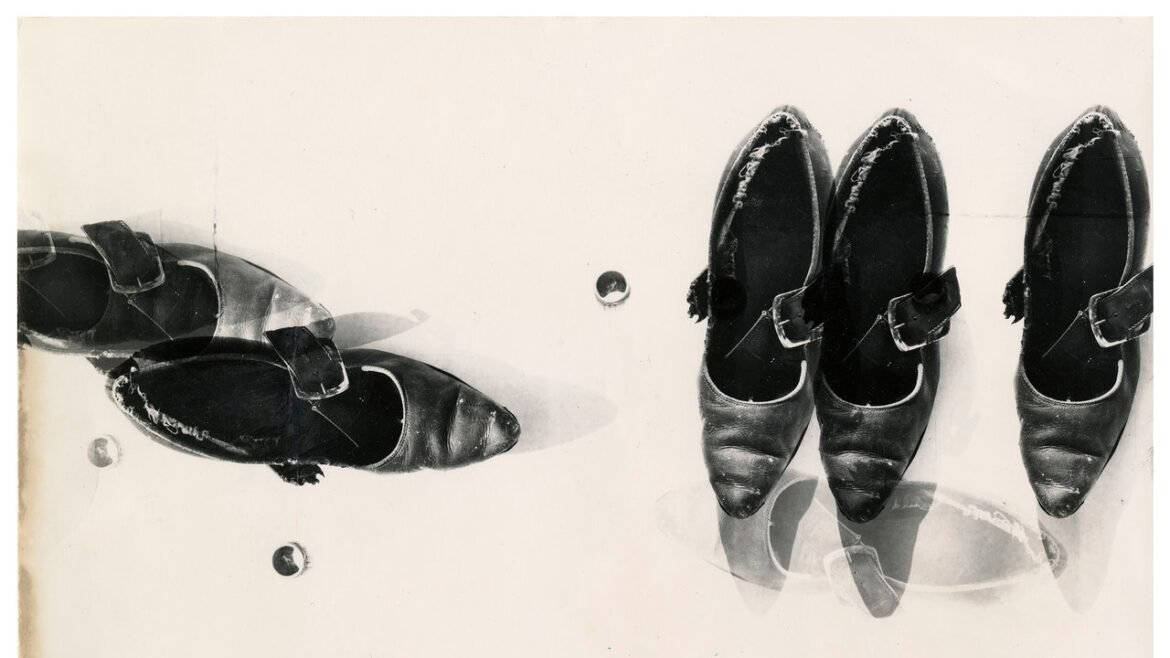

“Untitled (for B.C.),” 1973.

The work from those years has been little seen and largely unappreciated until now, with the release of an excellent book, “Jay DeFeo Photographic Work,” from Delmonico/D.A.P., and a jewel-box exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery. Both are revelatory. Seeing DeFeo’s photographs is like rediscovering a forgotten Surrealist—an intimate of Ray, Dora Maar, Max Ernst, and Raoul Ubac who had fallen off the art-world radar. But DeFeo’s connection to Conner, Wallace Berman, and the Bay Area post-Beat bohemian scene gives her work a funky, occasionally serrated edge. At Cooper, the pictures are, with one or two exceptions, all black-and-white and uniformly quite small; some are no bigger than snapshots. Their intimacy is seductive; the closer you get to each work, the more intriguing and unsettling it is. In an essay for the new book, Justine Kurland refers to the “airy weight” of DeFeo’s photographs, and that oxymoronic phrase strikes me as just right. Even when DeFeo is making pictures of solid, very ordinary things—a crab shell, a chandelier, a wooden staircase, a woman’s tattered shoe—the results look like they were captured in a dream, not ephemeral but haunted.