Activist shareholders play a central role in modern corporations, influencing the capital structure, business strategy, and governance of firms. Such “blockholders” range from investors who actively jawbone or break up firms to index funds that are largely passive in that they limit themselves to voting. In between, however, is a key group of blockholders that have historically focused on trading but have embraced activism as an established business strategy in the past few decades. Campaigns involving such “trading” blockholders have become ubiquitous, increasingly targeting large-capitalization firms; further, their attacks feature multiple activists, each with individual stakes that, in isolation, are unable to control targets. In this post, we ask three questions: (1) How do trading activists build stakes before an attack, while anticipating that other investors may have similar incentives? (2) Does the nature of strategic trading change relative to settings where activism is unlikely to occur? (3) Are there trade-offs between trading and the firm’s long-term value?

A Leader-Follower Take on the “Free-Rider” Problem

Activism is a costly activity in general: planning and executing big changes in companies requires research, consultants, and legal fees, all of which can add up to millions of dollars in expenses. A classic “free-rider problem” is at play: since the gains associated with any given campaign benefit all shareholders, there is an incentive to let others spend their own resources. All else equal (in particular, absent institutional differences across investors), shareholders with larger blocks have a greater incentive to incur those costs, as the extra value generated is applied to more shares. “Games of influence” naturally emerge: with many activists placing their eyes on the same targets, and block size determining their willingness to intervene in a firm, an activist might want to steer others to add value by affecting the profitability of block accumulation.

In a recent paper, we develop a model in which two activists decide how many shares to accumulate in a setting where (i) activists’ initial blocks are their private information (that is, positions have not been disclosed); and (ii) activists can invest to improve firm value. We consider the case in which initial blocks exhibit correlation, while trading is sequential: in the first period, a leader activist (she) submits a market order on the firm’s stock (alongside retail investors, who effectively camouflage her trade), while in the second period a follower activist (he) plays the role of the leader. In the third (and last) period, both activists take costly actions that determine firm value. Our leader must then evaluate how her trading will affect the firm’s value by influencing the follower’s subsequent trading opportunities. Thus, our steering dynamics are market-based, and hence less applicable to investors with portfolios in fixed proportions (for example, index funds); further, we abstract from environmental, social, and governance issues affecting firms’ values.

Trading Dynamics with Steering Motives

In a landmark paper, Kyle (1985) examined the question of how a trader with superior knowledge regarding a firm’s true value strategically transmits her information to the market via her trades. Two key insights emerge from the prolific literature that followed. First, the trader’s price impact sets limits on arbitrage, in a systematic way: while more responsive prices naturally induce less aggressive trades, the overall responsiveness of prices must be consistent with the information conveyed by the trader’s market orders—say, if the trader attempts to arbitrage an underpriced firm more aggressively by buying more shares, prices should respond more to order flows, and vice-versa. Second, the trader behaves in an “unpredictable” manner in equilibrium: the trader is always equally likely to be long or short relative to price quoted by market makers in any period—thus, the expected direction of her trade is neutral at all times.

Our model offers a new perspective on these insights. On the ‘limits to arbitrage’ dimension, price impact is also naturally at play, as it determines the expenses incurred while trading. But it is not the only force. Assume that the initial blocks are positively correlated—that is, leaders holding larger blocks initially are statistically indicative of followers having larger blocks too—and suppose that the leader accumulates a smaller block than anticipated by market makers who set prices. A surprisingly low order flow would induce the market maker to infer that the leader’s position—and that of the follower, because correlation is positive—are smaller than expected. From the perspective of the leader, therefore, such a move implies that the follower will face a lower quoted price when it is his turn to trade, effectively making block accumulation more attractive. As the follower acquires more shares, he necessarily makes a larger investment decision too, which the leader enjoys. In other words, the ability to influence firm value through the actions of other activists is a second force that influences the magnitude of market orders.

More formally, we construct an equilibrium in which the leader sells on average if positions are positively correlated initially, while she buys on average otherwise: in the latter case, a high volume is indicative of a large block by the leader, which now is synonym of a smaller position by the follower, and the same mechanism ensues. But this implies that the leader ceases to trade in an unpredictable way, as order flows gain non-trivial momentum in our equilibrium. Returning to our questions, the steering motive induces a leader activist to try to transfer costs to their followers by making their arbitrage opportunities more attractive (question 1): as followers acquire more stock, they develop more skin in the game. But to achieve this goal, the leader must trade in a way that departs from the traditional view on strategic trading that the leader trades in an unpredictable way (question 2).

Predictions and Correlation in Practice

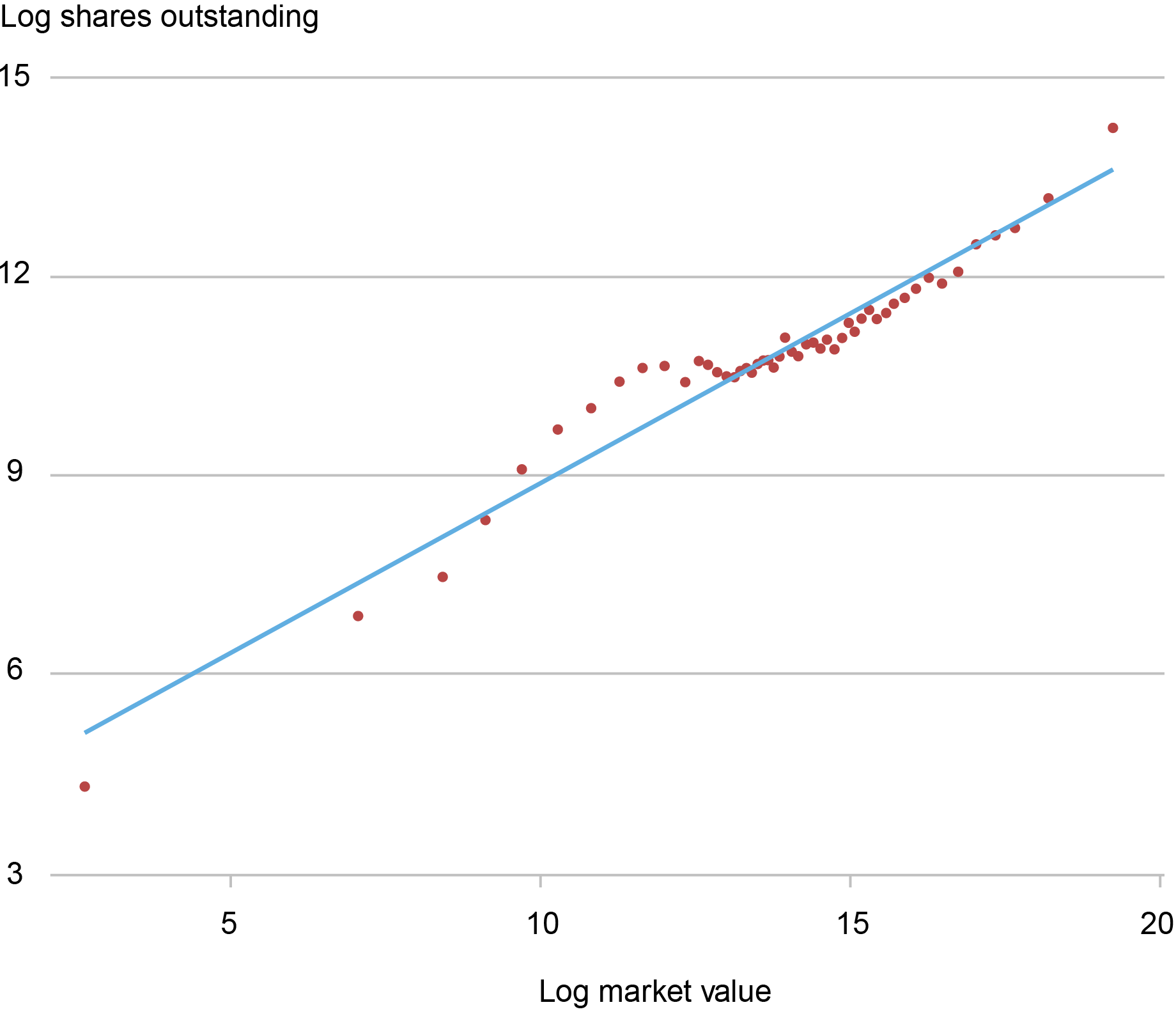

In our model, large terminal blocks—that is, post trading positions—are synonymous with high share values. Because the leader decreases/increases her terminal position when correlation is positive/negative, firms’ share values are lower/higher than if trading was not allowed, or activism was not at play. Thus, whether the steering motive exacerbates traditional free-rider motives, thereby reducing values (question 3), depends on the sign of the correlation. The latter can be connected with observable firm characteristics, allowing us to evaluate our findings. For instance, a mix of activists with long and short positions is more likely with negative correlation in our model: the higher share values that we predict are consistent with more stock appreciation arising for firms featuring investors with large short positions on its stock, as documented by some studies. Similarly, our work predicts that the additional value that activism brings should decline when moving from negative to positive correlation: this is in line with stock appreciation decreasing as market valuation transitions from low to high-cap firms—indeed, large-cap firms offer more scope for positive correlation because they tend to have more shares outstanding, as depicted in the chart below.

Shares Outstanding (Logs) and Market Values (Logs) for a Large Sample of Firms in the U.S. Stock Market

Source: Doruk Cetemen, Gonzalo Cisternas, Aaron Kolb, and S. Viswanathan (2023): “Activist Trading Dynamics,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports 1030, September 2022, Revised February 2023.

That said, we show that the presence of a leader always increases firm values relative to the case in which the follower acts in isolation, in line with evidence documenting that multiplayer engagements perform better than single-player counterparts: a potentially exacerbated free-rider motive does not offset the presence of an additional strategic leader investor who has vested interests in a firm.

Doruk Cetemen is an assistant professor of economics at the City, University of London.

Gonzalo Cisternas is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Aaron Kolb is an associate professor of business economics and public policy at Indiana University Kelley School of Business.

S. “Vish” Viswanathan is the F.M. Kirby Professor of Finance at the Fuqua School of Business, Duke University

How to cite this post:

Doruk Cetemen, Gonzalo Cisternas, Aaron Kolb, and S. “Vish” Viswanathan, “Leader-Follower Dynamics in Shareholder Activism,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 6, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/09/leader-follower-dynamics-in-shareholder-activism/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).