The two frogmen slipped into the dark cold waters of the English Channel and started swimming towards the shore. The sea was lumpy and the pair could feel the current pulling them further east than they wished. The rain was torrential and all they could see was the lighthouse beam as they swam hard for land. They came ashore opposite the village of La Rivière, staggering up the beach at a crouch, relieved that they were screened from the lighthouse’s beam by buildings and trees.

For a few moments Maj. Logan Scott-Bowden and Sgt. Bruce Ogden-Smith recovered their breath in the lee of some groynes. From the buildings above them they could hear revelry. It was the last day of 1943 and the Germans were seeing in the New Year with plenty of beer and song.

The two Englishmen set off down the beach, heading west for nearly a mile towards the original landing spot. The intelligence briefing had stated the beach was not mined. On this stretch of the Normandy coast the strong tides and shifting sand meant they would not stay in position. The rain was now nearly horizontal, a filthy night but a perfect one for their task.

Checking his map, Scott-Bowden announced that they had reached their place of work. They were to take samples of sand from the beach in an area designated in the shape of the letter ‘W’. The sand was collected by an auger, which, when inserted into the sand and given one half turn, dredged up a core sample. These were collected in twenty 10-inch tubes held in a bandolier worn by one of the men.

Ogden-Smith and Scott-Bowden worked swiftly, moving up and down the beach, taking samples but glancing now and again east to check that no Germans were clearing their groggy heads with a stroll down the beach. With their samples stashed in the bandolier, the pair left the beach and began wading through the breakers. But the wind had picked up and they were flung back into the sea. They tried again but without success. Apprehension began to rise. If they were caught on the beach with their bandolier the game would be up?

A Secretive Special Forces Unit

This was one of the most crucial moments of the war. Ogden-Smith and Scott-Bowden ran up the beach. With the lighthouse beam to help them, they worked out the wave pattern. On the third attempt they made it through the surf and swam furiously towards the recovery boat. Suddenly Scott-Bowden heard a cry through the wind. Turning, he saw Ogden-Smith waving an arm. “I swam back somewhat alarmed, thinking he had either got cramp or his suit had sprung a leak,” recalled Scott-Bowden. “When I got close, he shouted ‘Happy New Year!’”

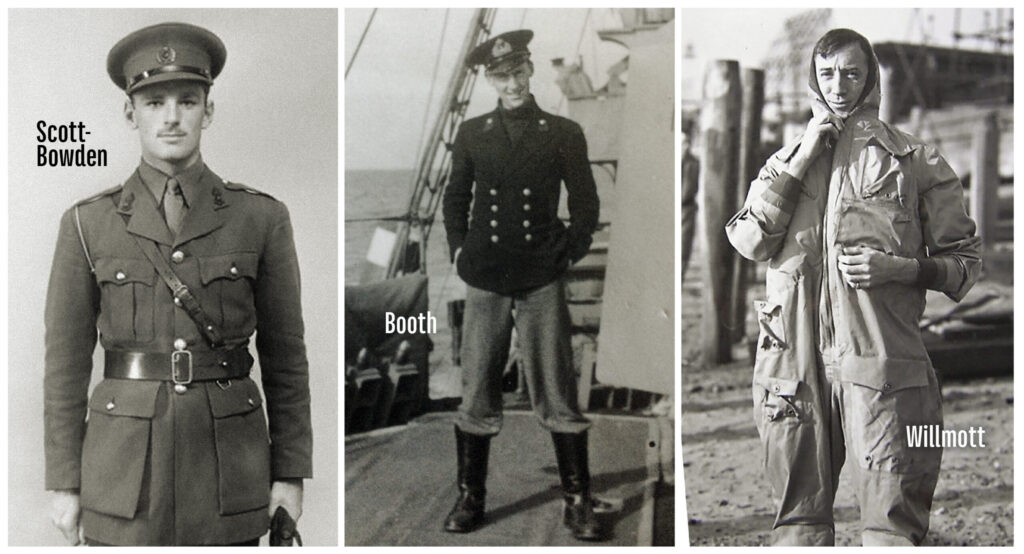

Bruce Ogden-Smith and Logan Scott-Bowden belonged to one of the most secretive special forces units in the British army. To those who served it was known by its acronym, COPP, short for Combined Operations Pilotage Parties.

(Gavin Mortimer Collection)

COPP was the brainchild of Lieutenant-Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Willmott, who had joined the Royal Navy between the wars, partly inspired by tales he’d heard as a young boy from his uncle Henry. He’d served in the First World War and had taken part in the disastrous Dardanelles campaign of 1915, when the Allies had attempted to knock Turkey out of the war by landing on the Gallipoli peninsula. It had been a bloody failure. Thousands of British, Australian and New Zealand troops were slaughtered attempting to establish a beachhead on clifftop ridges well-fortified by Turkish soldiers. Had the British planners been better briefed about the peninsula they might not have risked such an audacious amphibious assault. To Willmott’s dismay, the British military appeared not to have learned their lesson when the Second World War started. The Norwegian campaign in 1940, in which Willmott participated, was hampered by the Royal Navy’s ignorance of the fjords as they attempted to land British troops.

Beach Surveillance

In early 1941 Willmott was appointed navigation officer for a planned invasion of Rhodes, a strategically important island in the Mediterranean Sea. There was scant intelligence on the approach to the beaches or shoreline itself. Might there be sandbars or rocks just under the water? Were the beaches mined? Were they suitable for vehicles? Were there accessible exit points so soldiers could quickly move inland? Answers to these questions had to be found.

Willmott requested permission from Rear Adm. Harold Tom Baillie-Grohman, in charge of overall responsibility for planning the assault, to carry out a reconnaissance from a dinghy. It was a time in the war when the British, fighting a lone battle against the Axis forces, were at their most inventive out of necessity.

Small raiding units, dubbed ‘private armies’ were being formed with the encouragement of Prime Minister Winston Churchill: the commandos, the Long Range Desert Group and the Special Boat Section [SBS], the latter commanded by Maj. Roger Courtney, an adventurer before the war who had canoed the length of the White Nile in Africa. Courtney was only too happy to paddle Willmott ashore. Their reconnaissance proved invaluable, revealing perilous aspects of the shoreline that would have hampered any amphibious assault.

Private Armies?

Not all British senior officers approved of ‘private armies.’ Some regarded these units as unbecoming of the British military and it was another 18 months before Willmott was authorized to raise a naval reconnaissance force. It took the shambles of the Dieppe Raid in August 1942 to convince the British that better reconnaissance was imperative for future operations. Intelligence about the Dieppe coastline had been so poor that the British planners were reduced to studying prewar postcards of the coastline for clues about its topography. Three thousand Canadians and British commandos were killed or captured because of this ignorance, plus three killed in action, five wounded and three POWs of the 50 U.S. Army Rangers that took part while assigned to a commando unit.

Willmott’s unit gathered intelligence for Operation Torch, the Anglo-American invasion of Vichy-controlled French North Africa in November 1942. As a consequence, the following month the force was expanded and officially designated COPP.

(De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images)

Scott-Bowden was recruited to COPP as Willmott’s second-in-command in May 1943, a few months before Sub-Lt. Jim Booth. Scott-Bowden was a soldier but Booth volunteered from the Royal Navy, where he’d tired of life as a junior officer mine-sweeping in the North Sea. “I’d heard nothing of COPP prior to my arrival,” recalled Booth in a 2017 interview with the author. “But it was soon apparent that I was among a different breed. They were mad, really, but in a nice way. I think for most of us the motivation for volunteering was to do something different.”

New recruits to COPP underwent training at Hayling Island, off the south coast of England near Portsmouth. Willmot was ruthless in weeding out those men he judged to be deficient physically or mentally for his unit. “He was very nice but bloody tough,” said Booth. “During the autumn and winter of 1943, he led us in training every day. He was methodical in our navigational training because he knew the problems caused by poor navigation.” While Booth completed his training, Willmot and Scott-Bowden were told to report to Combined Operations HQ in London in December 1943.

Invading France

The planning for the invasion of France was underway. A 50-mile stretch of Normandy coast had been identified as a potential beachhead. But there were concerns. “Scientists had anxieties about the beach bearing-capacity of the Plateau de Calvados beaches for the passage of heavy-wheeled vehicles and guns, particularly in the British and Canadian sectors,” said Scott-Bowden. In ancient times there been peat marshes close to the sea. These had been covered with sand over the centuries, but the Allies feared that peat was often accompanied by clay, which could be catastrophic for a large invasion force.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington wanted a conclusive estimate of how much beach trackway would be required for the invasion force. Ogden-Smith and Scott-Bowden undertook a trial run on Dec. 22, 1943 on a beach in Norfolk, eastern England. It was an opportunity to gain valuable practical experience of using the auger to collect samples. It was also a chance for COPP to prove to sceptical Allied planners that they could do their work undetected by sentries. Having proved their point, the pair sailed to Normandy on New Year’s Eve and the real thing was as fruitful as the dress rehearsal.

“[Lt.] General [Omar N.] Bradley commander in chief of all the American [D-Day assault] forces… having heard that we had examined the British beach [Gold] wanted Omaha Beach—as it came to be known—to be examined too,” remembered Scott-Bowden.

Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was five miles west of ‘Gold’ beach. Bradley and his planners already knew it posed a formidable challenge to a putative invasion force. The beach was exposed, rising gently to a low sea wall, beyond which was a no-man’s land of marshy grassland. It was overlooked by bluffs, steep in places, which were cut by five valleys, the only exit points for vehicles and all heavily guarded by German concrete bunkers. COPP was instructed to bring back as much intelligence as they could about ‘Omaha’ beach in an operation codenamed Postage Able. Ogden-Smith and Scott-Bowden were again part of the team, accompanied by Willmot.

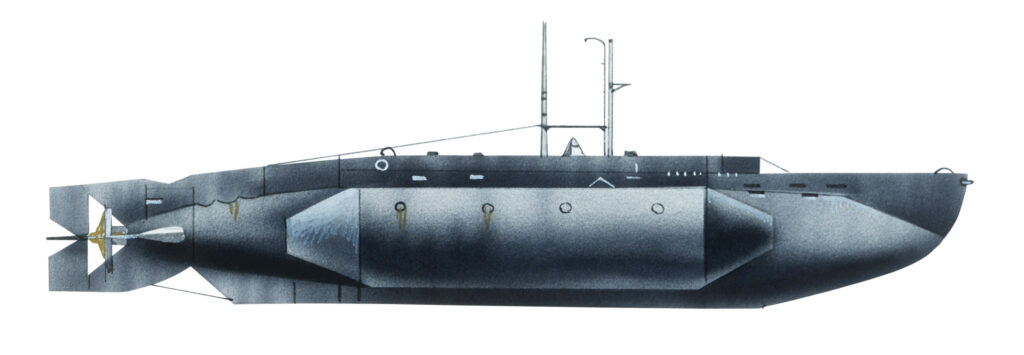

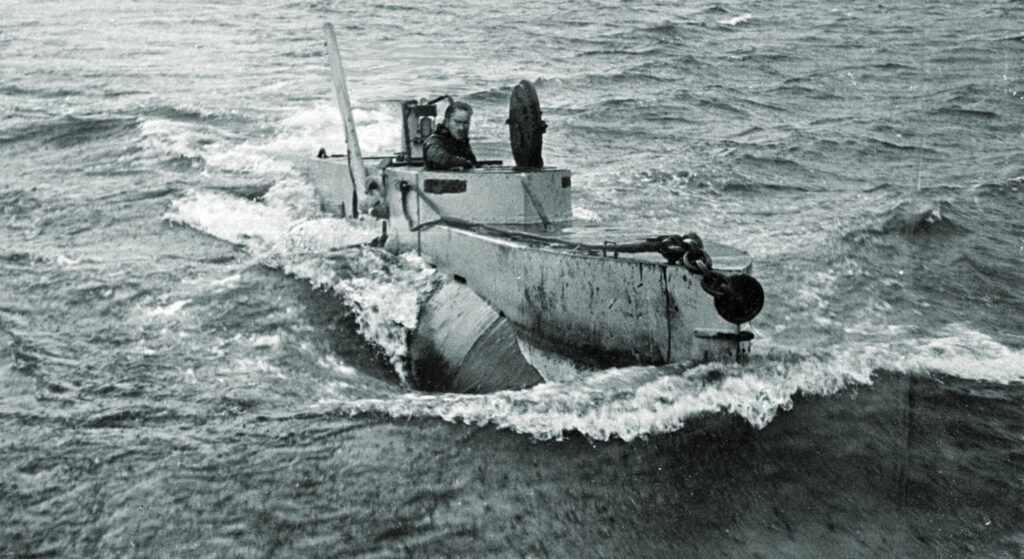

However, there was a significant difference to this mission compared to the one undertaken on New Year’s Eve. This time the audacious men would be traveling in an X-craft—a midget submarine that COPP had been conducting training on for several weeks in Loch Striven, a sea loch off the west coast of Scotland.

(Imperial War Museums)

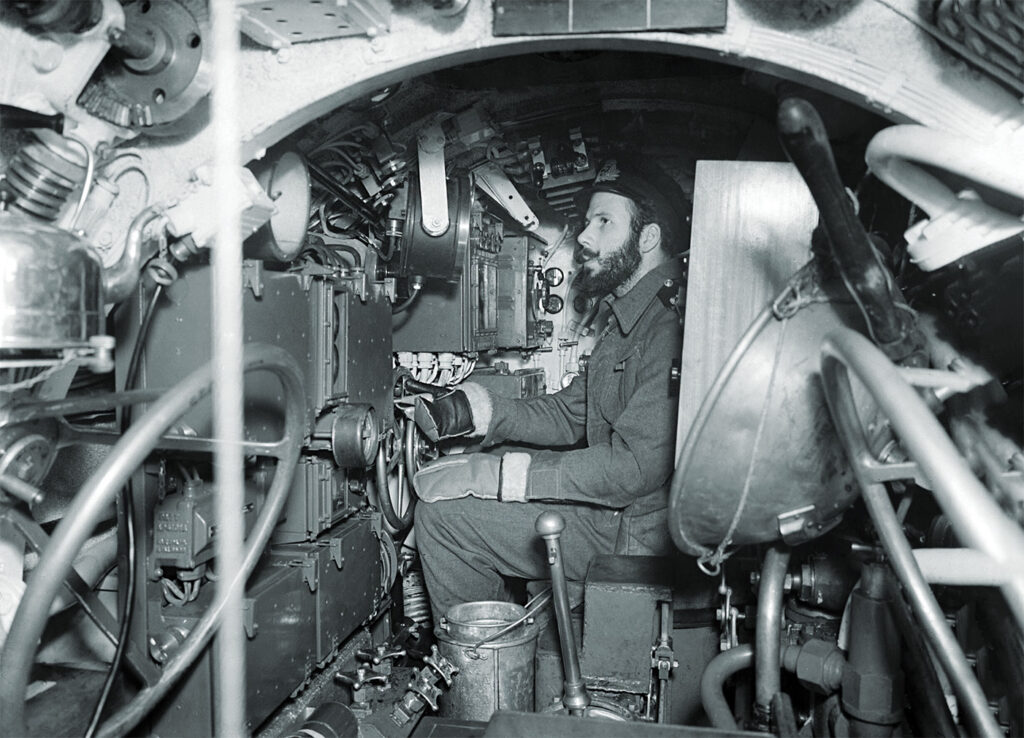

The X-class, or X-craft submarines were powered by 4-cylinder 42 hp diesel engines of the type used in London double-decker buses, and a 30 hp electric motor. Its maximum surface speed was 6.5 knots (a knot less when submerged). The midget submarines were usually crewed by three: the commander, pilot and engineer. Some also carried a specialist diver/frogman as a fourth member of the crew. “The X-craft were 52 feet long and 5 feet in diameter,” Jim Booth recalled, adding that they could remain at sea for to 10 days. The worst aspect of the midget submarines, certainly for the six-foot Booth, was their size. “The facilities were very cramped,” he remembered. “You had a bunk, cooking facilities, a gluepot for a hot meal, and you could just about stand.”

COPP had two midget submarines—X-20 and X-23—and it was the former that sailed from Portsmouth for Omaha beach on Jan. 17, 1944 under the command of Lt. Ken Hudspeth. It was a joint effort, his pilotage skills and the navigation of Willmot. “To reach the destination precisely, at [low] speed and in the strong cross-rides of Baie de Seine, was a measure of Willmott’s remarkable navigational skill,” commented Hudspeth.

At 2:44 p.m. on Jan. 18, the midget submarine was about 380 yards from the beach. It was nearly high tide. The vessel beached at periscope depth in 8 feet of water on the left-hand sector of ‘Omaha’ beach. Willmott took a couple of bearings to be sure of their position, then turned over the periscope to Scott-Bowden. “I took a quick general view and was astonished to see hundreds of [German] soldiers at work, and how hard they were working,” he recalled. “From our low-level view and pointing slightly up due to the slope of the beach, it was often possible to see under the camouflage netting and so verify the types of [gun] emplacement being constructed.”

Inside the Submersible

That night, Scott-Bowden and Ogden-Smith swam ashore to get a closer look. “We examined the beach with our augers over a wide area as planned,” said Scott-Bowden. The pair had special instructions to investigate the shingle bank at the back of the beach to determine if it might impede the progress of armoured vehicles. “It appeared to have been man-made and was above normal high water,” noted Scott-Bowden. “There were masses of wire immediately behind and a probable minefield. We each took one stone.” The next night the pair carried out another beach reconnaissance.

During daylight on Jan. 20 the midget submarine moved along the coast, observing different areas of the beach through the periscope. Then in the late afternoon they sailed for England. It was another two hours before Hudspeth felt it safe to surface, to the relief of the five men on board (the fifth was the engineer officer). Willmott recorded in his journal that the air was “very bad (none fresh for 11 hours) and everyone showed signs of distress.”

They reached Portsmouth at 6:30 p.m. on Jan. 21—after no less than five days inside X-20. Several high-ranking officers were on the quayside to greet them but when the rear hatch was opened “the reception committee took a large step back.” Scott-Bowden didn’t blame them. The stench had been unbearable. A midget submarine was no place for a soldier.

(Imperial War Museums)

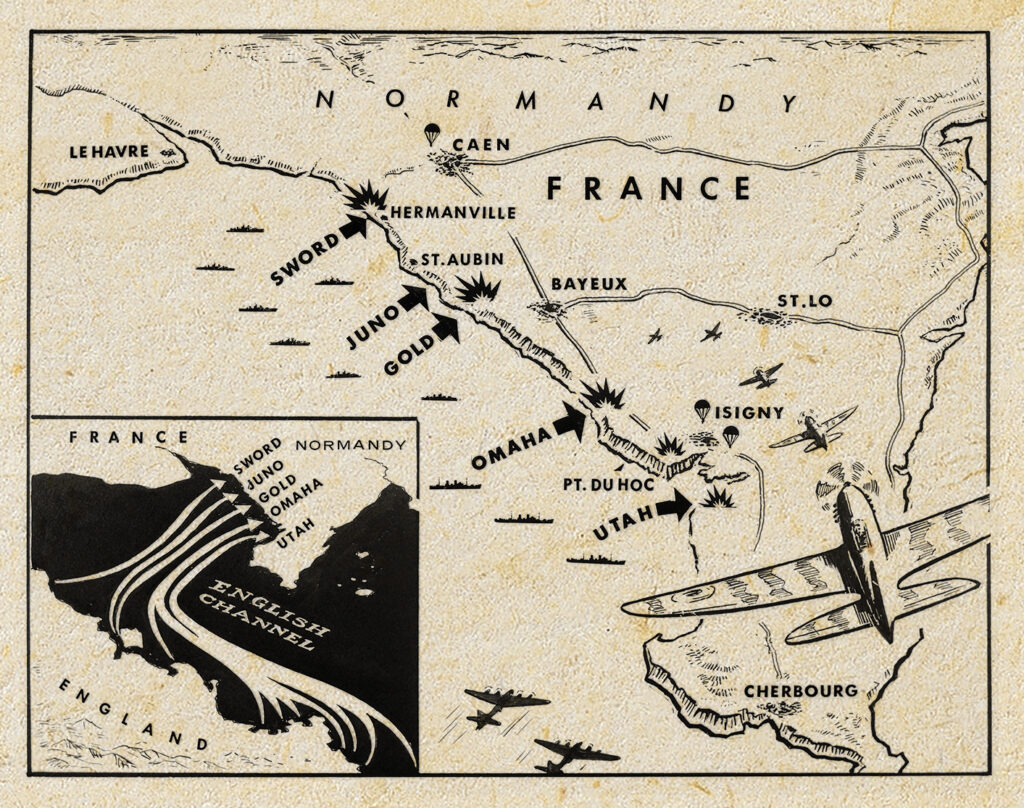

The midget submarine had gathered vital intelligence on what became known as Omaha Beach for the planning for D-Day. Its role in assisting with the invasion of Normandy was not over. A new destination for X-20 was Juno Beach, the middle of the three Anglo-Canadian landing sectors with Gold to the west and Sword to the east. Arriving off the coast on June 4, the submarine acted as a beach marker for the main amphibious assault as they approached on the morning of D-Day.

COPP’s other midget submarine, X-23, was tasked with performing a similar task at Sword beach, the eastern extremity of the invasion task force. The crews of both vessels had been ordered to Portsmouth with their craft at the end of May. “We booked into the wardroom and so we knew it [the invasion] was imminent,” said Jim Booth. “Everything had been done in the greatest secrecy, however, and while we had done a lot of training, we had no clue to the date of the invasion or the location.”

On the morning of June 2, the skipper of X-20, Lt. George Honour, assembled his crew, which comprised Booth, Lt. Geoff Lyne (chief navigator), George Vause (engineer), and First Lt. Jimmy Hodges (diver). The invasion was on, he told them. They would depart in the evening. Their operational orders were to sail the 90 miles to Normandy and then lie on the bottom of the Channel a mile off Sword beach until the early hours of D-Day on June 5. Then they would surface, erect their masts with their lights shining seaward, activate their radio beacons and guide in the invasion fleet.

Switching on the Beacons

Booth’s job was to climb into a dinghy and erect the masts and switch on the beacons. The operation was codenamed “Gambit,” a word Honour explained to his men was a chess move in which a piece is risked so as to gain advantage later. The men laughed sardonically.

The rest of the day was one of frenetic activity as they loaded the midget submarine with equipment: 2 small CQR anchors, three flashing lamps with batteries, several taut-string measuring reels, two small portable radar beacons, an eighteen-feet-long sounding pole and two telescopic masts of similar length. Twelve additional bottles of oxygen were hauled down the access hatch, to complement the vessel’s built-in cylinders, and three RAF rubber dinghies were also brought on board.

A handful of submachine guns and revolvers (and false identification papers) were stashed inside the sub in the event they were forced to abandon the vessel and make for Nazi-occupied France. At 9:40 p.m., X-20 and X-23 sailed out of Portsmouth and rendezvoused with two naval trawlers that towed them part way across the Channel.

The submarines slipped their tows at 4:35 a.m. June 3 and headed independently towards their respective beaches. X-23’s orders was to position itself at the point where the amphibious Duplex Drive Sherman [DD-swimming] tanks were to be launched onto Sword Beach. The pressure on the shoulders of Lt. Lynne, the navigator of X-23, was therefore immense: a slight error in position could have appalling ramifications.

The chief pre-occupation of X-23’s skipper, George Honour, was their oxygen supply; to conserve it as best he could he carried out a procedure every five hours of what submariners call “guffing through”—coming to periscope depth and raising the induction mast, then running the engine for a few minutes to draw a fresh supply of air through the boat. This brought obvious risks, particularly as they would lying just off the enemy coastline.

(Bettmann/Getty Images)

At 8:30 a.m. June 4 Honour wrote in his log: “Periscope depth, ran to the East. Churches identified and fix obtained.” They had arrived at their position off Sword beach. The churches they could see were those at Ouistreham. Booth peered through the periscope. On the beach was a group Germans playing football. “Poor buggers don’t know what’s going to hit them,” he muttered.

Enough Oxygen?

In less than 24 hours the invasion would be underway—or so they thought. But when they surfaced at 1:00 a.m. Monday June 5 and hoisted their radio mast, they received bad news. “The postponement was sent out in a broadcast,” remembered Booth. “There were several messages and the phrase to let us know invasion was off was ‘Trouble in Scarborough’. [Scarborough is a coastal town in eastern England]. That caused a bit of tension because we didn’t know the length of the postponement and we weren’t sure we would have enough oxygen.” X-23 remained on the surface until 3:00 a.m. June 5. The men enjoyed the stiff wind on their faces and the fresh air in their lungs.

Reluctantly they climbed back inside their 52-foot submarine, closed the hatch and bottomed. Honour said the lack of oxygen inside the midget submarine left him feeling like he’d drunk “a couple of stiff gins.” He added: “It was murky, damp and otherwise very horrible.” X-23 surfaced at 11:15 p.m. on Monday, June 5. They began their wireless watch. The weather was still foul.

The crew believed the invasion would again be postponed, but the message they received confirmed it was on. They dived once more, then surfaced at 4:45 a.m. on Tuesday June 6. The sea was too rough for Booth to launch his rubber dinghy so instead he rigged up the lights above the submarine. The lights flashed the letter D for Dog for 10 seconds every 40 seconds from 140 minutes before H-hour—the start time of the assault.

“We had a few problems with the boat because it was rocking and rolling,” recalled Booth. “We secured the main one, a green light, and also some red and white lights, and then because it was so cold and miserable out on deck we went down below and put the [tea] kettle on.” The radio beacon had also been activated. There was nothing else to do but have a cup of tea and wait. The tension was as unbearable as the foul air they breathed. Aircraft began bombing the German coastal positions. Soon the guns of the naval armada joined the bombardment.

Invasion Day

Booth and his comrades went back on deck just as dawn broke on June 6. For several minutes they peered south through the murk, straining to see the armada they knew was coming their way.

“Suddenly we saw them,” recalled Booth. “It was a case of ‘bloody hell, look at that lot’! It was literally ships as far as the eye could see. A very spectacular sight.”

As the invasion fleet loomed into view another danger confronted X-23—being sunk or shelled by one of their own vessels. The commanding officer of the destroyer, HMS Middleton, Lt. Ian Douglas Cox, was standing on his ship’s brige when “a small submarine suddenly loomed out of the faint mist.” He and his lookout assumed it was an enemy vessel. Middleton gave orders for ‘full ahead.” “As we gathered speed to ram her, a figure stood up on the conning tower waving a large White Ensign,” he recalled. “We laughed nervously and sheared away.”

X-23 avoided any further unpleasant encounters and made its way to HMS Largs, the headquarters ship, where it rendezvoused with a naval trawler. A relief crew exchanged places with Booth and his comrades, who gratefully boarded the trawler. The operation had lasted 72 hours—of which 64 had been spent underwater. The men craved fresh air as much as they did sleep. Operation Gambit had indeed been a risk, but above all it had been a success.

The COPP force and the midget “X-craft” submarines were vital to the success of the D-Day landings, anddeserve more credit than has yet been given to them. Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of German-occupied France on the Normandy coast, was the single most complicated human endeavor undertaken before the “computer age,” and its success is due to the incrediblecoordination of all branches of service of the Allied powers.

Popular history and films tend to focus on the June 5–6, 1944 airborne operations and the deadly ordeal the infantry assault troops suffered and endured at bloody Omaha Beach, but the ultimate goal of the operation—establishing a secure Allied foothold on the European continent in the face of fierce German resistance, was only achieved by the total commitment and supreme effort of every single member of all Allied forces taking part—on land, sea and in the air. This article recounts only one of those efforts.