Still, the Egyptian channel may hold more sway with Hamas leaders in Gaza, because Egypt, as Baskin put it, “controls the lifeline of the Gaza Strip.” As an example, he cited Egypt’s successful pressure on Hamas to stop supporting Islamic State activities in northern Sinai in 2018.

So far, Israel’s wartime cabinet, which is made up of Netanyahu, Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, and Benny Gantz, a centrist opposition leader, has presented Israel’s ground incursion into Gaza as improving the chances that the hostages will be released. “If there is no military pressure on Hamas, nothing will progress,” Gallant told family members of abductees last week. No doubt, Israel’s military operation is squeezing the Hamas leadership, which has been hiding out in a maze of underground tunnels since the war began. But there is no knowing just how Hamas will respond to such pressure. As Baskin put it, “Will they agree to a deal or will they start doing, God forbid, what the Islamic State did with the prisoners that they were holding, and execute them on camera?”

In the meantime, U.S. patience with the Israeli offensive appears to be wearing thin. The U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, has said that “far too many Palestinians have been killed” and warned that there can be no reoccupation of Gaza once the conflict ends. According to Amos Harel, a military analyst for the left-leaning Haaretz newspaper, the window in which the U.S. tolerates military action will likely close sometime between Thanksgiving and Christmas. After that, Israel may find itself diplomatically isolated, with irrevocable damage wrought on Gaza.

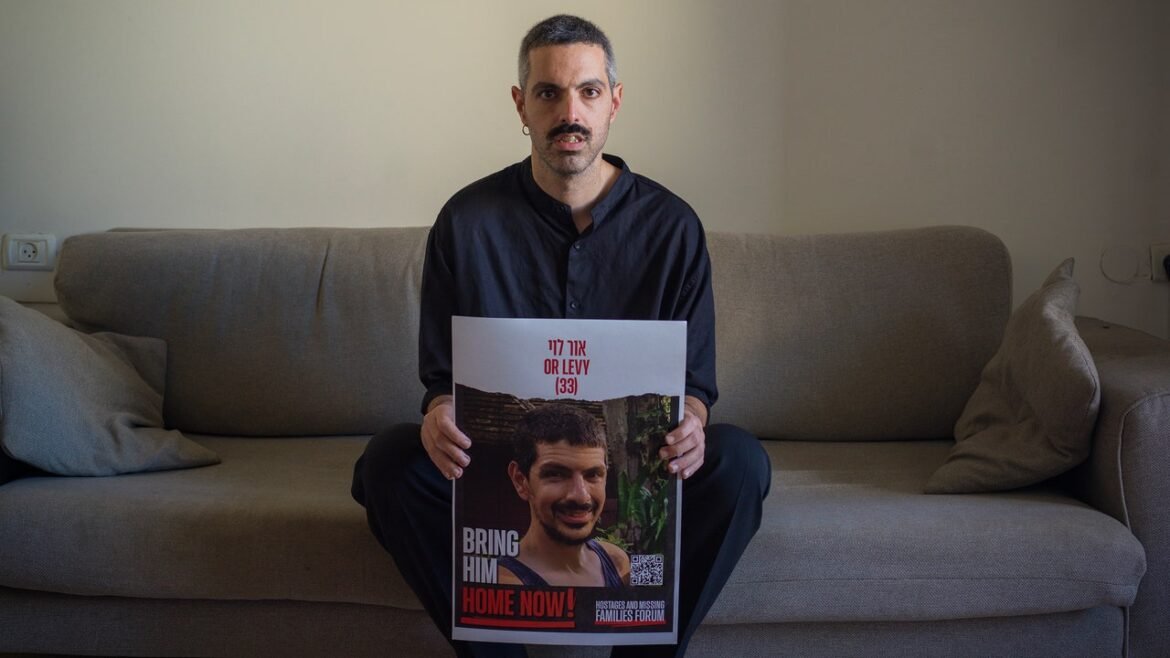

Levy, who works as a filmmaker, has watched Israel’s military campaign with a growing pessimism that is rooted in his profession. “Images of destruction are much more dramatic than those of some guys coming home,” he said. “It’s clear that the politicians prefer the image of the strongman, and it’s just not right. To be strong is to take care of your citizens and their security—not to crush or to kill.”

From left: Liri, Roni, and Gili Roman, siblings of Yarden Roman-Gat, who is being held hostage in Gaza.Photograph by Michal Chelbin for TIME

Like Or Levy, Yarden Roman-Gat is a hostage being held in Gaza with a toddler waiting back home. On October 7th, militants broke into Kibbutz Be’eri, near the Gaza border, and forced Yarden, her husband, Alon Gat, and their three-year-old daughter, Geffen, into a pickup truck at gunpoint. As they reached the border, three of the four militants got out of the vehicle; Yarden and Alon noticed that their driver was unarmed. Signalling to each other, they opened the passenger doors, jumped out, and started running; Yarden, who is thirty-six, held Geffen in her arms. Gunfire soon erupted all around them, according to Yarden’s older brother Gili. Yarden, running barefoot, felt that she was falling behind and handed the child to her husband, while she ducked into the nearby woods, covering her head with her arms. That was the last Alon saw of his wife. He emerged with Geffen from another clearing in the forest twelve hours later, in total darkness, without food or water. He began an hours-long journey by foot back to Be’eri, all the while searching in vain for Yarden.

Alon returned to his kibbutz to find it ravaged: houses burned to the ground; more than a hundred kibbutz members murdered. Among those killed, he learned, was his mother. His sister was also taken hostage. Now he is left to care for his daughter alone, not knowing the fate of her mother.

Meanwhile, Yarden’s parents’ home, in a tree-lined suburb of Tel Aviv, has been converted into what her three siblings call a “war room” for bringing back their sister. When I visited last week, a large paper roll was spread out on the carpet for Geffen, who had drawn little stick figures. Yarden’s brother, her sister, and six of her friends sat around a nearby table in silence, each glued to a laptop and tasked with a different assignment: from reaching out to foreign diplomats to deciding on a strategy for the month ahead.

“It’s what we know how to do: function,” Yarden’s sister Roni, who is twenty-five, said.

Reflecting on her older sister, Roni cringed slightly. “She is such a private person. She would have hated seeing her picture” plastered on posters all over the country, Roni said. She went on: “I try to think about her as little as possible. Otherwise, it’s constant: I’m drinking coffee. What about her—when did she last eat? I’m sleeping in a bed. What about her—where is she sleeping? I’m playing with Geffen. What about her? This encounter with reality makes me not want to do anything, like shower or eat, but I know that I have to stay sane for her.”

In one respect, at least, Yarden’s family stands apart from some of the other hostages’ families: Yarden is a dual national, holding both Israeli and German citizenships (her grandmother is a Holocaust survivor); many others are not. Over all, the group of hostages is highly global, and, while the Israeli government has been slow to provide families with information on their loved ones, foreign governments have sprung into action. Biden, on a recent visit to Israel, spent more than an hour with the families of fourteen Americans who are missing in Israel, and said, of the meeting, “We’re not going to stop until we bring them home.” The government of Thailand has been in contact with officials in Qatar and Egypt about the release of twenty-three of its citizens, who had been working as farm laborers in Israel. The leaders of Britain, France, and Germany also held meetings with relatives of their nationals in Israel. Germany’s Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, met with a group that included Yarden’s siblings, who later travelled to Berlin, where they spoke at a rally in front of twenty-five thousand people.

One of the more controversial proposals being floated in recent weeks calls for the release—independent of a broader deal—of the roughly fifty dual nationals who are being held in Gaza. This proposal, first reported in the Times, has led to murmurs in Israel about a kind of “selektzia,” or selection process, whereby the lives of Israelis who hold second citizenships may be more prized than the lives of others. That term is a loaded one in Hebrew parlance, harking back to the sorting of prisoners at Nazi concentration camps.