Leanne Blinzler Noe was eight years old and living in the Philippines with her family when the Japanese attacked the islands on the day after Pearl Harbor. She and her sister, Ginny, hid out with German nuns at a convent in Manila for several years during the war. Then, in March 1944, the Japanese forced them to enter Santo Tomas Internment Camp, where they joined thousands of already imprisoned Allied civilians, including their dad, Lee Blinzler.

Noe, now 90, endured near starvation and her fear of the Japanese guards, even though adults in the camp tried to instill a state of normalcy with school (not her favorite thing) and entertainment evenings (very fun). On February 3, 1945, the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division liberated the camp. To this day, General Douglas MacArthur remains Noe’s hero.

How did you end up in the Philippines in the 1930s?

My father was a gold engineer working at the Dewey Mine near Yreka, California. This was during the Great Depression and the mine closed. He heard from a friend there was a boom going on in the Philippines, so in the fall of 1936, he moved our young family—my mother, my younger sister, Ginny, and me—to Marinduque. I was three years old.

But then my mother died soon after we arrived; we believe it was TB. Our father moved my sister and me to Holy Ghost College in Manila, where a German order of nuns ran a school, while he stayed in Marinduque.

In November 1939, milling operations in Marinduque stopped, and my dad found work at Balatoc Mine outside the mountain retreat of Baguio, in northern Luzon. He lived at the mine, while Ginny and I resided at Holy Ghost Hill, the nuns’ summer home, where we were the only two boarders.

(Courtesy Barbara Noe Kennedy)

Do you remember when the Japanese first attacked the Philippines?

It was December 8, 1941. Ginny and I went to church that morning at the cathedral in Baguio. In the middle of the consecration, we heard loud thumping sounds. The priest put down the chalice and told everyone to go home. He advised that we hide in ditches if we heard planes again. We returned to the convent, where everything was quiet. Some Igorots [indigenous Filipinos] came to the door to sell strawberries and sugarcane. While I was washing the fruit in the kitchen, I heard the same loud pounding that we had heard while at church—the Japanese were attacking Baguio! The bombs terrified me, but Ginny and one of the nuns ran outside and watched the attacking planes.

How did you escape from Baguio?

After the Japanese attack, my dad arranged a ride for my sister and me in a company car to the safety of Manila, promising he would follow soon. Two men from the mine, armed with pistols, drove us down the mountain. As we approached the flatlands, the men surveyed the landscape, very alert, looking for enemy soldiers who had reportedly landed on nearby beachheads at Lingayen Gulf. Later we learned the car’s trunk contained the mine’s gold bullion, which was whisked away by submarine to Australia and then the U.S.

In Manila, we tried to return to Holy Ghost, but they couldn’t take us. So the men dropped us off at a European orphanage, until conditions permitted us to return to Holy Ghost at the end of January. It’s possible the U.S. Army was using part of Holy Ghost as a hospital.

How did you end up in the prison camp?

In January 1944, the Americans began to win the war in the Pacific. The Japanese Military Police took control of the camp, and life became more miserable for the prisoners. On March 10, the enemy, who knew about us by then, decided Ginny and I should be brought into Santo Tomas. We traveled there by calesa [a horse-drawn carriage], were inspected by the Japanese at the front gate, and moved our few belongings to Room 55A in the Main Building, which was packed with 26 women and children.

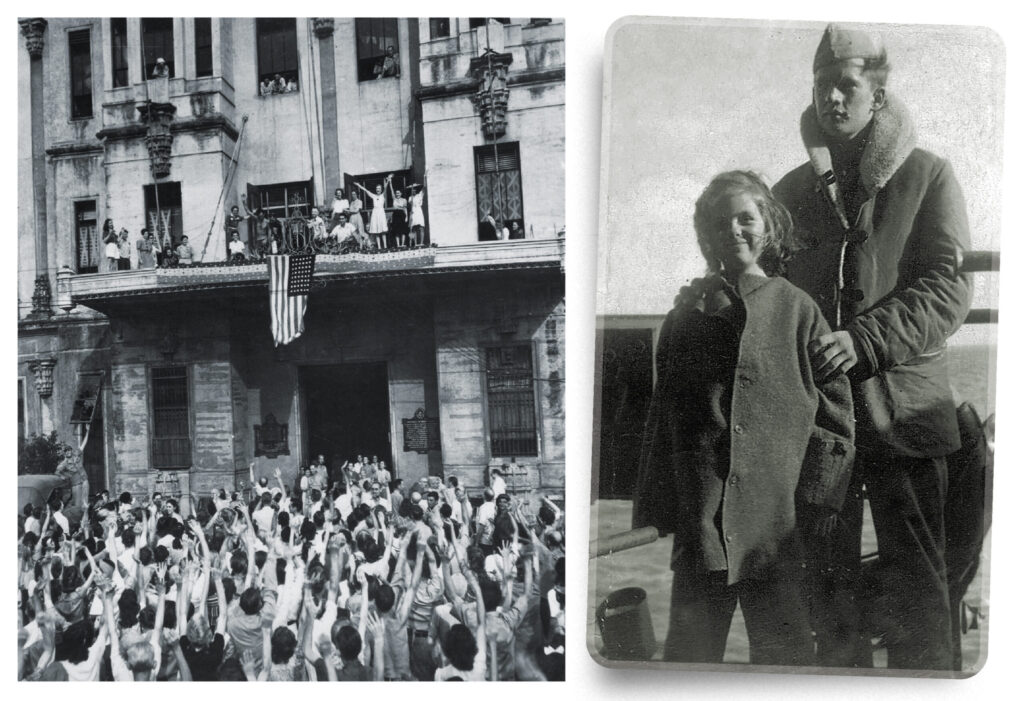

(U.S. Army/Interim Archives/Getty Images)

Tell us a little bit about the camp.

Santo Tomas is Asia’s oldest university. It was founded in 1611. A high wall surrounds its cluster of buildings on all sides. That’s where we were interned.

Our days were organized into activities, beginning with roll call. Sometimes we stood for hours outside our room, while the Japanese soldiers inspected us.

We all had responsibilities. I washed our sheets in an outside tub once a week and left them to dry in the sun to chase away bedbugs. Among the day’s most important events was chow time when, about an hour before food was ladled out, I would stand with our dad’s and my meal tickets and our tin cans, waiting for the line to open. (Ginny ate in the children’s line.) Breakfast and dinner were often a watery rice stew called lugao.

In our free time, Ginny and I and our friends climbed on a bamboo jungle gym at the playground. As food became scarce, the playground was converted into a vegetable garden. We played Monopoly and, believe it or not, War. One day I found a tired rubber dolly in the trash. I took it, washed it, and hand-sewed clothes for it from scraps.

Dave Harvey, a Shanghai entertainer and professional comedian, established “theater under the stars,” with a screen and wooden stage. There were movies, acts, quizzes, singing, and Harvey’s comedy routines. We had lots of fun on those evenings.

Did you have to go to school?

Yes! Even in prison, we attended school, five days a week. One advantage of imprisoning Manila’s expats was the high caliber of professional teachers available to teach classes. I remember studying ancient history, Tagalog, and Japanese.

Why did MacArthur move so quickly to liberate Santo Tomas?

Supposedly, American intelligence received a message from a clandestine radio in Santo Tomas stating the Japanese were preparing to execute us. Upon landing at Lingayen Gulf in January 1945, MacArthur demanded that the 1st Cavalry move onto Manila as quickly as possible. After liberating the military POW camp of Cabanatuan, a “flying column” charged south.

(Courtesy Barbara Noe Kennedy)

What do you remember about your liberation?

On February 3, 1945, planes were flying low overhead—not typical bombers but tiny Piper Cubs with blue stars on silver backgrounds…Americans! The planes left, and we had a 6:00 p.m. roll call and early bedtime. I heard low rumblings, gunfire in the distance, and the black sky lit up like the northern lights with tracer bullets.

Then someone said an American tank was striking through the wall outside camp. Ginny and I rushed down to the front hall of the Main Building and watched from the crowded steps. Soon, a tank came into view. Oh my gosh, we were so excited. The vehicle came to a halt, and several tall and healthy-looking men emerged, looking like good-natured giants.

Was that the end of it?

No. The Battle of Manila raged all around us, so even though we were liberated, we had to stay at Santo Tomas.

A few days after liberation, Ginny and I snuck out to the front of the Main Building during nap time to meet two soldiers who had promised to give us Hershey bars. All of a sudden, shells rained on the building. Ginny and I were hit, and soldier James Smith carried us both inside. We later learned that the other soldier, Steve Bodo, was killed.

We were transported by army ambulance to a government building in Quezon City that was being used as an evacuation hospital. I didn’t know it then, but I had a piece of shrapnel lodged in my jaw. My mouth was so swollen, I could hardly eat. Ginny’s lower arm was so damaged by shrapnel that it later required 90 stitches. Her wound was packed with Vaseline gauze and the pain was so excruciating she had to be put out to change it.

One night the enemy shelled the evacuation hospital. Some of us sought shelter in the hallway and prayed the rosary, our voices rising up when the shells were closer and louder. An army nurse named Nancy joined us. I was surprised to see someone in the army so frightened. The next morning, we saw that one of the shells had lodged in the building, but without exploding.

(U.S. Army/Interim Archives/Getty Images; Courtesy Barbara Noe Kennedy)

How did you return to the United States?

I think because of our injuries we were on the first trip out, around March 13. We were flown in a military plane to Leyte, where we slept in tents on the beach. We swam in the water; one day I saw a torso—gruesome—but for the most part we had a grand time.

They gave us immunizations and put us on the [transport ship] USS Admiral W.L. Capps. We slept on triple-deck bunks and enjoyed lots of food, including candy and oranges. The ship zigzagged in a convoy and, 18 days after leaving Leyte, we approached the Golden Gate Bridge. I thought our ship was so tall it might hit the bridge!

Where did you go then?

Our mother’s sister, Jerry Edwards, who lived in Berkeley, greeted us at the dock. She had agreed to take Ginny and me into her care as we forged ahead into our new American life. Two years later, we headed back to the Philippines to be with our dad, who had returned to the mine, but that’s another story!