One of the many iconic photographs taken on the Gettysburg battlefield by Alexander Gardner’s photographic team was the heartbreaking image of the bloated corpse of a horse. The unfortunate animal was one of the wheel pair, and it died still harnessed to a shattered limber, the deadly contents of the limber chest scattered about. Freshly covered graves are nearby, possibly those of the drivers and artillerymen who manned the light 12-pounder Napoleon cannon.

Through the haze, a line of army wagons and artillery vehicles are parked behind the wreckage, trees showing just above the white canvas covers. While the appalling destruction of battle remains untouched where it fell, the war goes on as soldiers wait in the background for orders to continue the pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia to the Potomac River.

Gardner’s photographers took the image on or about July 6, 1863. When Gardner published his Photographic Sketchbook of the War later in 1863, he titled the image “Unfit for Service.” The scene conveys the traumatic image of death and destruction of man and animal alike, and is a stoic reminder of the cost of war.

Aside from its poignancy, the image leaves some questions unanswered. To what battery did this limber and horse belong? What happened at this location that caused such destruction? How did this wreckage remain untouched for so many days after the battle ended?

Where Was It?

Though the image was published in the Sketchbook and as a stereoview after the war, this photograph did not receive widespread attention until years later when an overly enhanced version captioned “Shattered Caisson—Gettysburg ‘Peach Orchard’” first appeared in The War Memorial Book (1894). Miller’s Photographic History of the Civil War (1911) published a much clearer view of the scene that revealed the line of vehicles beyond the wreckage, what appears to be part of an orchard, and, upon closer examination, the roof line and chimney of a house.

But whose house could this be, so close to the fighting? In 2010, several of the Licensed Battlefield Guides at Gettysburg speculated it was the Peter Rogers house that stood along the Emmitsburg Road, but did the remainder of the landscape match the fields and trees? Of the candidate houses that stood along the same road, one alone stands out: the Joseph Sherfy house adjacent to the famous Peach Orchard.

(Library of Congress)

(Courtesy John S. Heiser)

Sixty-three-year-old Joseph Sherfy and his wife, Mary, had lived on this farm since 1844, where he managed a flourishing fruit business. The enterprising farmer experimented with the best type of peaches and apples to grow in Adams County’s somewhat shallow soil, his large mature peach orchard producing enough fruit to accommodate a canning business in a building behind his brick home. Sherfy had planted new trees north of the established orchard, its trees just ready to produce when war came to their doorstep on July 2, 1863.

The Sherfys fled their home that day only to return four days later to discover their house damaged by shell fire, personal belongings scattered in the yard, the barn burned to the ground, crops trampled, fences torn down, and most of his peach trees in his recently planted “young orchard” damaged beyond salvage, as he recalled in his 1872 damage claim.

Graves of the fallen were everywhere, and the bloated remains of more than a dozen dead horses lay where they fell in the wheat and meadow opposite their home. Army wagons and artillery vehicles continually passed through the Sherfy fields, stopping briefly to allow congestion to clear the roads ahead. Details from Union regiments had picked up and stacked discarded small arms and equipment, leaving behind material that could not be reused. In the field opposite their home was a disabled limber chest, shells still lying nearby, as Mrs. Sherfy told a visitor in 1886. Worried of the danger, Mr. Sherfy and a farmhand buried the ordnance in the field, taking care to mark the location. That disabled limber was most likely the same photographed by Gardner’s team that warm summer morning in 1863. The sad wreckage was left lying in the center of Sherfy’s field on the eastern slope of the ridge from the Emmitsburg Road to Plum Run.

(Lucas Deaver (Alamy Stock Photo))

With the location of this historic photograph identified, a more important question needs to be answered: to whose battery did this limber belong?

The “Great Artillery Duel”

During the desperate July 2 fighting on this farm, numerous Union artillery batteries were overrun, guns captured, and limbers lost to Confederate hands. Only the arrival of fresh Union troops and ensuing counterattack saved those precious guns, which were drawn off the field after nightfall by exhausted teams of artillerymen and uninjured horses. Only one gun, a 3-inch ordnance rifle and limber belonging to Consolidated Battery C&F, 1stPennsylvania Light Artillery, was left behind and would be captured by Confederates the following day.

Yet this limber and ammunition in the historic photograph was for a 12-pounder “Napoleon”—the fearful bronze gun favored by many artillerymen for its dependability and stopping power. Obviously, there were unknown circumstances that left this shattered limber on the field. If it was not from a Union battery, which Confederate battery stood at this site?

Beginning in 1895, the U.S. War Department Commission, composed of veterans of the battle, initiated the masterful and difficult task of marking every unit position in the park with a tablet bearing a brief narrative of their participation at Gettysburg. Commissioner William Robbins, a veteran of the 4th Alabama Infantry who faced the fierce combat before Little Round Top on July 2-3, 1863, struggled to document the activities of Confederate units, especially batteries in Major Mathias W. Henry’s Artillery Battalion of Hood’s Division, Longstreet’s Corps. Reports from many of the battery commanders and Major Henry himself did not survive the conflict and could not be found in U.S. War Department records in Washington, D.C.

As Robbins later confessed, he constructed battle narratives for some units based on the activities of their fellow units and without those precious reports, narratives on several tablets were woefully incomplete. One of these cases stands out—the July 3, 1863, activities of several batteries in Henry’s Battalion, notably Captain Hugh R. Garden’s South Carolina Battery, the “Palmetto Light Artillery.”

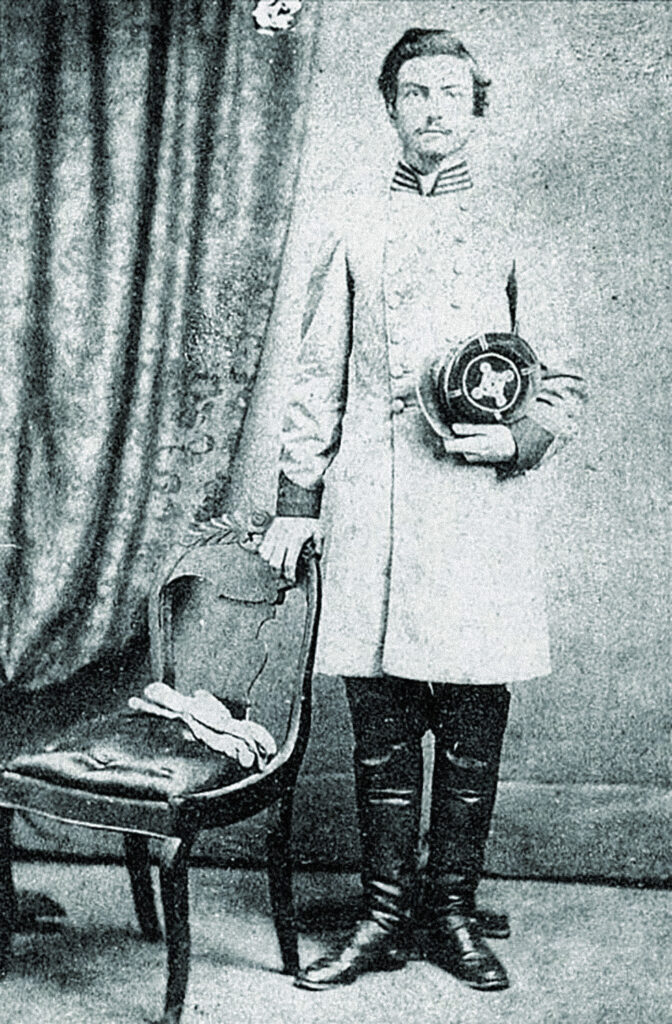

Born in Sumter, S.C., in 1840, the dashing Hugh Richardson Garden had just completed his studies at South Carolina College when war erupted. He volunteered for service as a private in Company D, 2nd South Carolina Infantry, during which time he was recognized as a model soldier and promotions followed. Through the influence of family and military officials, he received an appointment by the state in 1862 to raise and command a newly formed battery of artillery destined to join the Army of Northern Virginia.

Garden successfully recruited and organized a full battery and within months was in Virginia, where he was assigned to Major Henry’s Artillery Battalion. Having seen only minimal action prior to the Gettysburg Campaign, the Palmetto Light Artillery of four guns (two 10-pounder Parrott Rifles and two 12-pounder Napoleons)arrived on the battlefield on July 2 but remained in reserve as the fighting raged against the Union left flank centered on the now famous Sherfy Peach Orchard.

(National Archives)

At mid-morning the following day, Garden received orders to march his battery with other sections of artillery from Henry’s Battalion to an impressive line of Southern guns with other artillery battalions of Longstreet’s Corps. The fieldpieces stretched from the Peach Orchard northwesterly to Spangler Woods and Seminary Ridge opposite the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. Tasked with opposing Union artillery strategically placed on Little Round Top, Garden unlimbered his Parrott rifles in the Peach Orchard on the right flank of Major B.F. Eshleman’s Artillery Battalion, the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, and with the report of two signal guns at 1 p.m., Garden’s cannons began their participation in the great barrage that preceded Pickett’s Charge.

July 3, 1863, would haunt Garden for years to come. “On the day of Pickett’s Charge,” he wrote to Lloyd Collis in 1901, “I was sent about a mile to the left of my first position near the turnpike, immediately on the right of the Washington Artillery, and engaged Big Round Top during the first part of the great artillery duel. While thus engaged the chief of Gen. Longstreet’s staff, who was on the pike observing the effect of the artillery fire, ordered me to cease firing… and to move by section to the left of the peach orchard and advance in echelon across the plain. I obeyed the order, but only one section of my battery, under Lieutenant [Alexander] McQueen, made the advance, for when it moved obliquely to the left and went into position at a point down a gentle descent (as I can never forget) about 200 yards to the left of the peach orchard, and about 300 yards at least in front of our line of artillery, the attention of the opposing artillery was drawn to our fire, and within ten minutes every horse and man was killed—or wounded.”

After passing through the orchard and down the slope, Lieutenant McQueen’s artillerymen unlimbered the two 12-pounder guns in an open field, loaded, and opened fire on Union infantry of Brig. Gen. George Stannard’s Vermont Brigade sweeping around Pickett’s masses crowding toward the Angle. Though their fire and those of a handful of other pieces from Eshleman’s Battalion that also advanced was at first effective, it also unleashed a torrent of counterbattery fire from Union guns aligned on the well-established line on the lower portion of Cemetery Ridge.

At his post behind one of McQueen’s guns, artilleryman J. Merrick Reid recalled: “No sooner had flame and smoke gushed after the hurtling shell that Round Top Hill became a veritable seething volcano of destruction, emitting dense volumes of smoke, lurid tongues of flame hurtling metal missile that hissed or shrieked through space and burst with deafening peals. The ground was ploughed and torn and great clouds of dirt and debris thrown up everywhere. Man after man went down with his death hurt…not a horse was left to move a wheel.” Reid was horrified when a single Union shell mortally wounded two comrades in front him, spattering his uniform with blood and gore. Within minutes, the Union batteries had driven off the Confederate cannoneers from the guns that had been pushed forward from Eshleman’s Battalion and then turned their attention on Garden’s solitary section of Napoleons. From their post on Cemetery Ridge, Captain Patrick Hart’s 15th New York Battery of four Napoleons sent explosive shell after shell at the outnumbered South Carolinians.

Near Hart’s guns stood Captain Edwin Dow’s 6th Maine Battery, which also focused its four 12-pounder guns on the exposed Southerners. “A light 12-pounder battery of four guns ran some 400 or 500 yards in front of the enemy’s line,” Dow reported soon after the battle, “so as to enfilade the batteries on our right.” After driving off the artillerymen from these guns that belonged to Eshleman’s Battalion, Dow focused his attention on McQueen’s two guns, alone but defiantly firing from their exposed position. “We opened with solid shot and shell…and succeeded in dismounting one gun, disabling the second, and compelled the battery to leave the field minus one caisson and several horses.”

The sweeping concentration of Union artillery from the summit of Little Round Top to the center of Cemetery Ridge would prove too great for the outnumbered Confederate artillery. “No man flinched his duty,” Merrick Reid recalled many years after. “Exhausted, bleeding, ammunition spent, comrades prone, six horse dead or dying, further effort futile, our gallant officer, the calmly brave McQueen, himself faint and bleeding, ordered the pitiful fragment to seek protection from the infernal death sluice.”

Aghast at the destruction, Captain Garden raced to the site to confront the seriously wounded Lieutenant McQueen, who could barely manage the orders for his men to seek shelter. Those still able turned and ran to the comparative safety of the Emmitsburg Road, leaving behind guns, limbers, wounded comrades, and horribly wounded horses thrashing about in their harnesses. “I took volunteers and fresh horses in to remove my men and gun(s),” Garden continued. “After two attempts we succeeded, under the same concentrated terrific fire, made more terrible by the explosion of caissons and the fire overhead of our friends in the rear.”

(Library of Congress)

The Confederate infantry assault failed, and there was little more that could be accomplished. Lee sent orders through Longstreet to withdraw his troops from their advanced position to form a line of defense on Seminary Ridge. Captain Garden’s desperate mission was still underway when those orders arrived.

As the Southern batteries hurriedly limbered and hobbled to the rear, Garden realized that with Union guns commanding the field and Union skirmishers seen advancing toward the abandoned artillery line, further efforts to bring off additional equipment was fruitless. A shattered limber and chest, horse harnesses and other equipment, all too dangerous to retrieve, remained to mark the location where his guns had fought so deadly a duel.

The following day, details of Union troops gathered small arms from the field while others buried the dead where they had fallen. Southern ordnance, still dangerous despite the soaking rains that covered the area, remained untouched for others to recover.

Thus, the scene remained to be captured by the photographer’s camera on or about July 6, 1863, where Hugh Garden’s section of 12-pounder guns from his Palmetto Light Artillery, only a few days before, had made the suicidal stand at Gettysburg. Placed in context with Garden’s description, compassionately penned in a letter years after the war, this place on the battlefield was indeed where “all hell broke loose.”

More important, this photograph provides historians with a more complete evaluation of the somewhat curious story of Major M.W. Henry’s Battalion in the massive bombardment before Pickett’s Charge, its disturbing aftermath, and the shocking cost of war. And while we all strive to further describe and understand the image labeled “Unfit for Service,” perhaps the most suitable sentiment was paid by Garden himself, an attempt to honor the sacrifice paid by his battery day: “I have always thought that as Pickett’s charge marked the high-tide of the Confederacy, the advance of that solitary section in obedience to what I understood to be Gen. Longstreet’s order to advance the artillery marked the high-tide in the greatest artillery duel in history.”

John S. Heiser began his career with the National Park Service in 1976 at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. He transferred to Gettysburg National Military Park in 1980, where he held numerous positions until 1997 when he was appointed as historian to manage the park’s library, website, and other duties, a position he held until his retirement in 2020. He still resides in Gettysburg. The author wishes to gratefully thank Scott Fink and Scott Brown for their research assistance with this article.