Wage growth has moderated notably following its post-pandemic surge, but it remains strong compared to the wage growth prevailing during the low-inflation pre-COVID years. Will the moderation continue, or will it stall? And what does it say about the current state of the labor market? In this post, we use our own measure of wage growth persistence – called Trend Wage Inflation (TWIn in short) – to look at these questions. Our main finding is that, after a rapid decline from 7 percent at its peak in late 2021 to around 5 percent in early 2023, TWin has changed little in recent months, indicating that the moderation in nominal wage growth may have stalled. We also show that our measure of trend wage inflation and labor market tightness comove very closely. Hence, the recent behavior of TWIn is consistent with a still-tight labor market.

TWIn: Measuring the Persistence of Wage Inflation

To recover the persistent (“core”) component of wage inflation, we rely on a framework that combines worker-level data with time series filtering techniques. Here, we briefly summarize the methodology. Additional details can be found in our previous Liberty Street Economics post and in this paper.

We start from monthly data on wage growth across seven different industries from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Following the well-established methodology of the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker, we define wage growth as the median percent change in the hourly wage of individuals observed twelve months apart. We then estimate a model in which wage growth in each industry is decomposed into the sum of a persistent component and a noise term that captures transitory variation and measurement error. Both persistent and noise components are further split into common and industry-specific terms to accommodate potential cross-sectional correlation.

Importantly, we estimate the persistence of unobserved monthly wage growth from year-over-year wage changes. Our measure therefore tends to lead year-over-year wage changes, which are influenced by wages in the past twelve months by construction. This produces a timely measure of wage growth, useful to detect turning points in real time.

Will Strong Wage Growth Last?

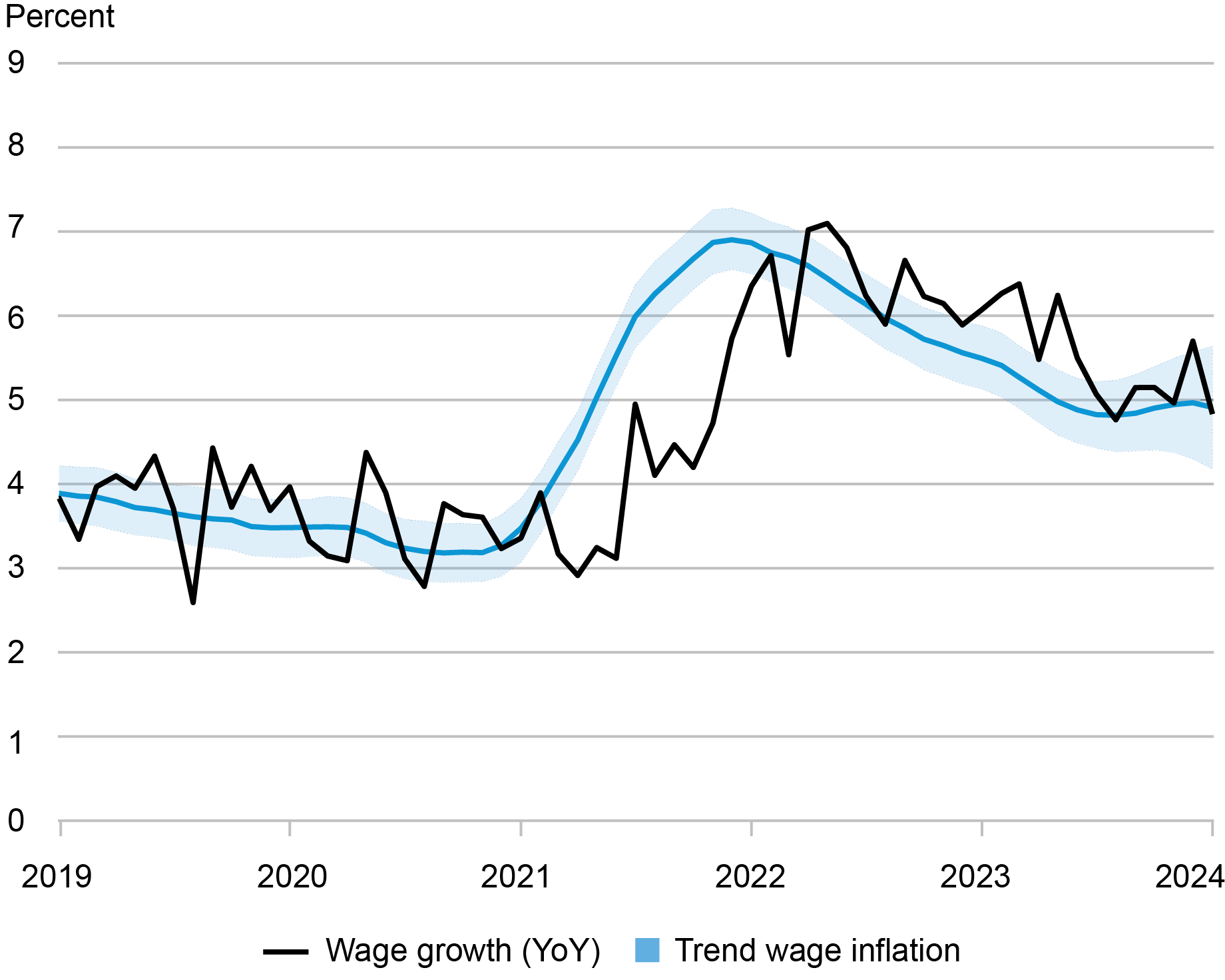

The chart below shows our estimated trend (solid blue line) together with the realized twelve-month wage growth defined as described above (black line). The shaded area around the trend is a 68 percent confidence band that captures the uncertainty associated with the estimates. We highlight two main takeaways.

Wage Growth as Measured by TWIn Peaked in Late 2021, Then Moderated

First, after remaining stable between 2019 and 2020, the trend increased markedly at the beginning of 2021, nearly doubling over the course of the year. As such, a large chunk of the wage growth we saw over the course of 2021 appears to have been persistent. It is worth stressing once more that the trend extracted by the model is expressed in terms of annualized monthly wage growth, which explains why it leads the actual year-over-year wage growth series in the chart.

Second, the model suggests that the trend may have peaked in the early months of 2022, and then started declining. The moderation in TWIn flattened out mid-2023 and has remained stagnant since. However, the shaded areas still illustrate considerable uncertainty. The recent slowdown estimated by our model indicates it cannot be ruled out that wage growth will continue to be markedly higher in the near-term than it was before the pandemic.

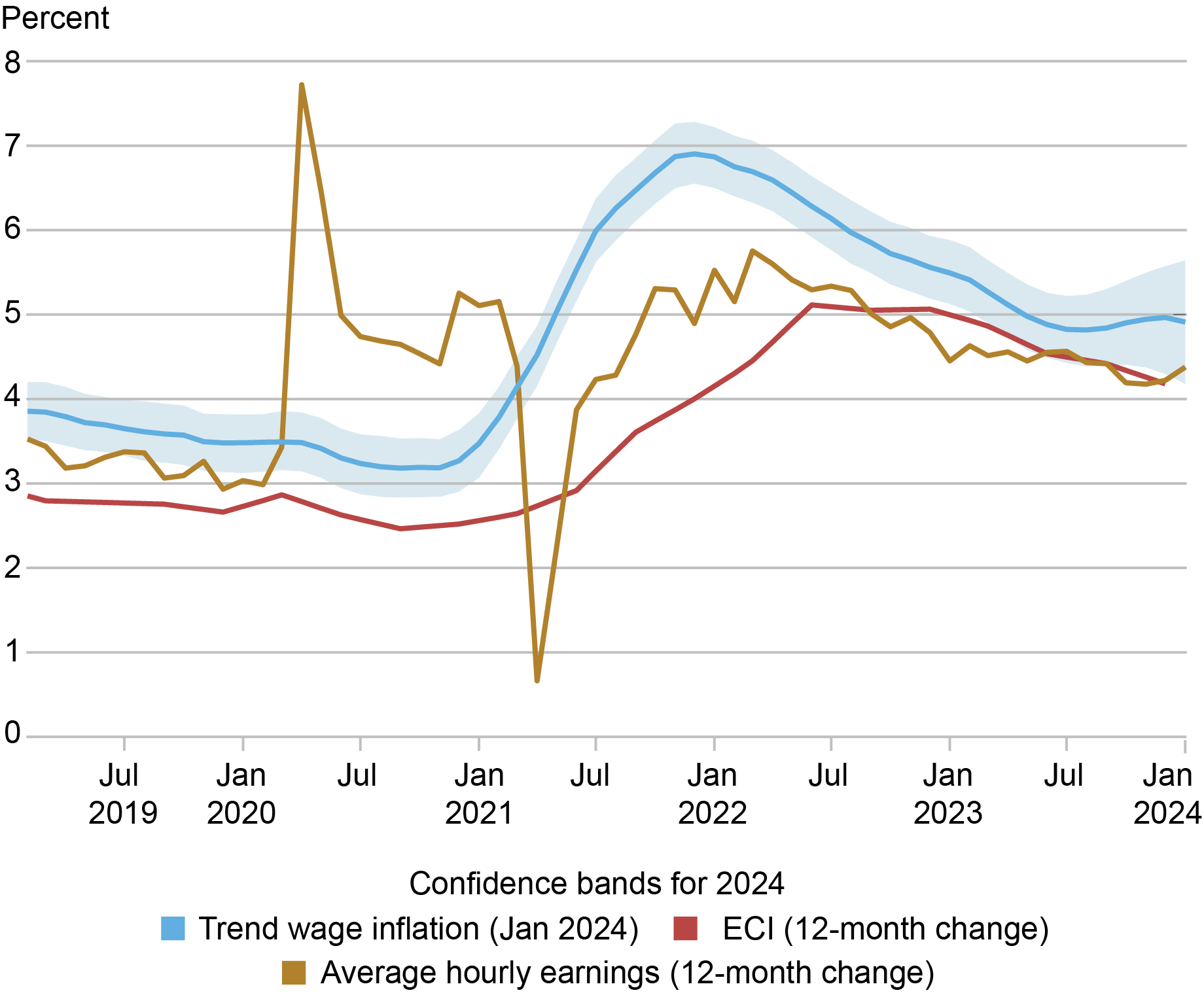

However, alternative indicators of wage growth have been sending mixed signals in recent months, as we show in the chart below. The employment cost index (ECI), shown in red, has been trending downward, though the most recent data point for this measure is for the last quarter of 2023. The deceleration in average hourly earnings has stalled recently and the growth rate even ticked up in January. Finally, as discussed, TWIn has been mostly flat in the last six months. These mixed signals reinforce the point on the uncertainty around our TWIn estimates moving forward.

Alternative Indicators of Wage Growth Are Sending Mixed Signals

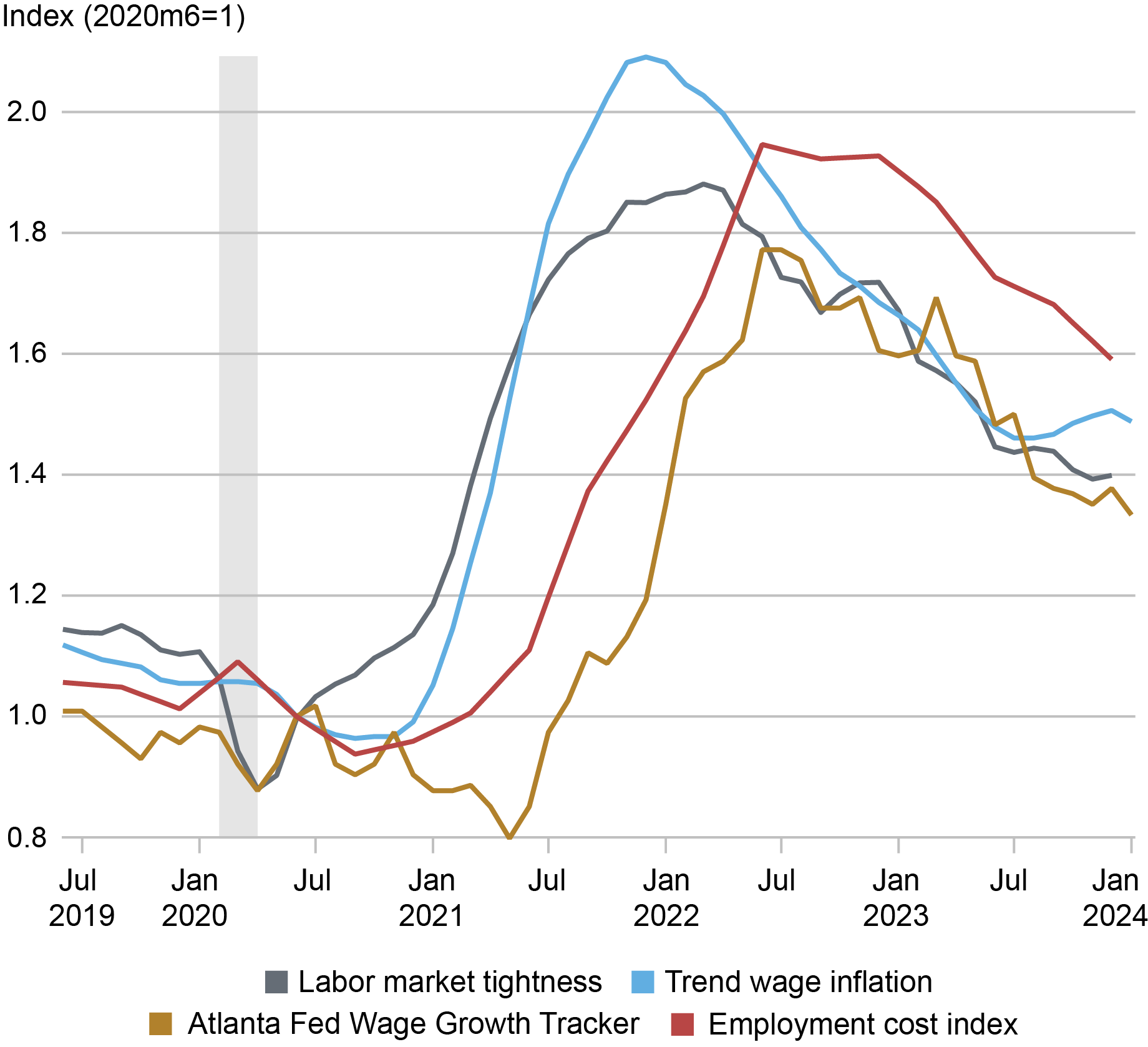

Wage Growth Persistence as a Signal of the Labor Market

Our filtering approach to time aggregation delivers a measure of wage inflation that is timelier than alternatives. We show this in the chart below, which compares the recent evolution of our measure (blue), the employment cost index (red), and the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker (gold). Our measure of Trend Wage Inflation always leads alternative measures of wage growth: importantly, it is better aligned to labor market tightness. We illustrate this point in the chart where the grey line denotes labor market tightness, defined as job openings divided by the labor force.

TWIn and Labor Market Tightness Tend to Move in Tandem

Our measure of Trend Wage Inflation therefore represents an additional signal on the current state of the labor market. When labor market conditions are tight – that is, when there are a lot of vacant jobs relative to job seekers – wage growth is high, as firms need to post higher wages to attract and retain workers. TWIn and labor market tightness both peaked toward the end of 2021. Thereafter, both measures have gradually fallen, as the imbalance between job openings and job seekers has gradually diminished.

What are the implications of persistent nominal wage growth? First and foremost, TWIn adds to other indicators pointing to a still-tight labor market. Many labor market indicators, such as job vacancies or the rate at which unemployed workers find jobs, are still at or above their pre-pandemic level. In addition, persistently elevated nominal wage growth may have repercussions for price inflation, although it may also be the result of wages in nominal terms catching up with previously high price inflation. Our approach offers a way to look under the hood of short-run, noisy fluctuations in wage growth. While considerable uncertainty remains, our estimates point to persistent wage growth that is still above its pre-pandemic levels.

Martín Almuzara is a research economist in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Audoly is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Augustin Belin is a research analyst in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Martin Almuzara, Richard Audoly, Augustin Belin, and Davide Melcangi, “Will the Moderation in Wage Growth Continue? ,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 7, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/03/will-the-moderation-in-wage-growth-continue/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).