It’s 2003, and Cat Power exists in rarefied air. The word “chanteuse” is bandied about, an exotic label for an American singer-songwriter on an indie label. And, yes, Cat Power—a.k.a. Chan Marshall—is beguiling. But the Francophone descriptor fails to conjure the dust her voice kicks up, the grit and moan that hang in the air after each song. As Hilton Als noted in a review that August, a Cat Power show can be shambolic, with Marshall flipping through channels that only she is privy to, occasionally landing on a song. For the listener, the journey is both thrilling and desultory, like hanging out sober while your friend trips on mushrooms.

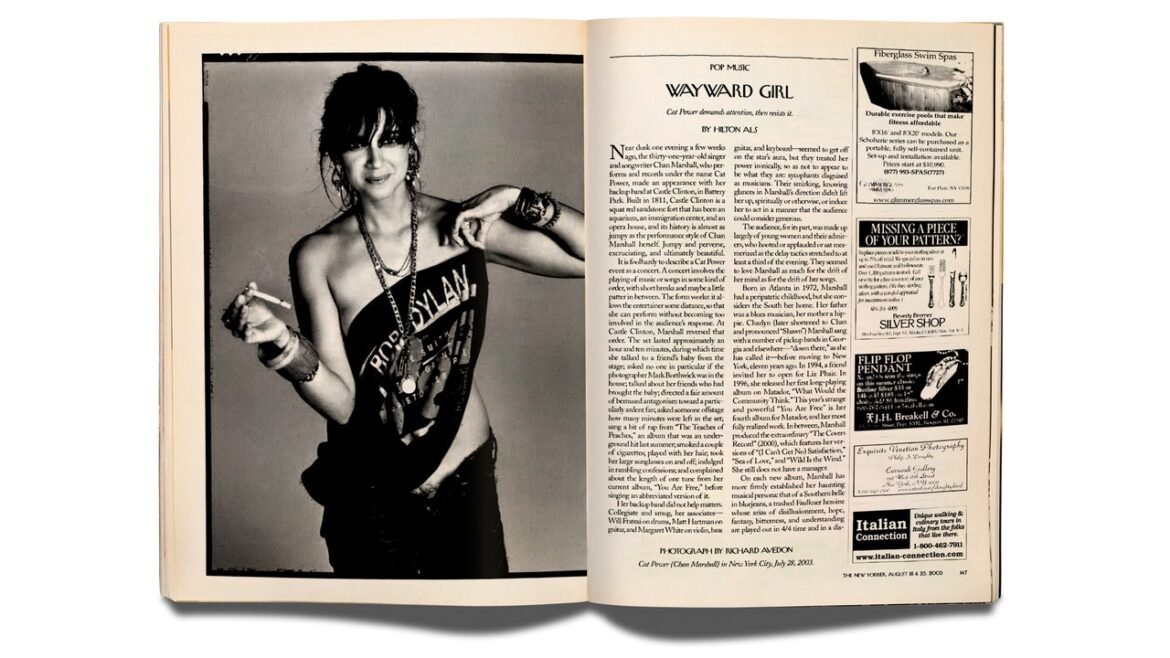

Richard Avedon’s accompanying portrait discards any notion of Cat Power’s caprice; there’s no bewilderment or confusion on display, no underlying contradictions. Here she is, in totality. It could be day or night—but who cares, because the scene seems to be happening right now. Your brain wants to dissect the image. Is she arriving home or going out, dressing or undressing? The Bob Dylan shirt is neither on nor off her body; she’s not covering Dylan, he’s covering her. Displaying. Discarding. Stop, it’s only a shirt. The unbuttoned jeans are going down, coming up; the pubic hair is staying either way. Take in her morning-after smoky eye. That half smile. Try squeezing between Cat Power and Avedon’s lens. The space is slippery, inaccessible; you’re not sure you were even invited. In the end, you’re the one who feels unknown, as temporary as the ash on Marshall’s cigarette. Everything else is Cat Power. ♦