Kendra Pierre-Louis: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Kendra Pierre-Louis, in for Rachel Feltman.

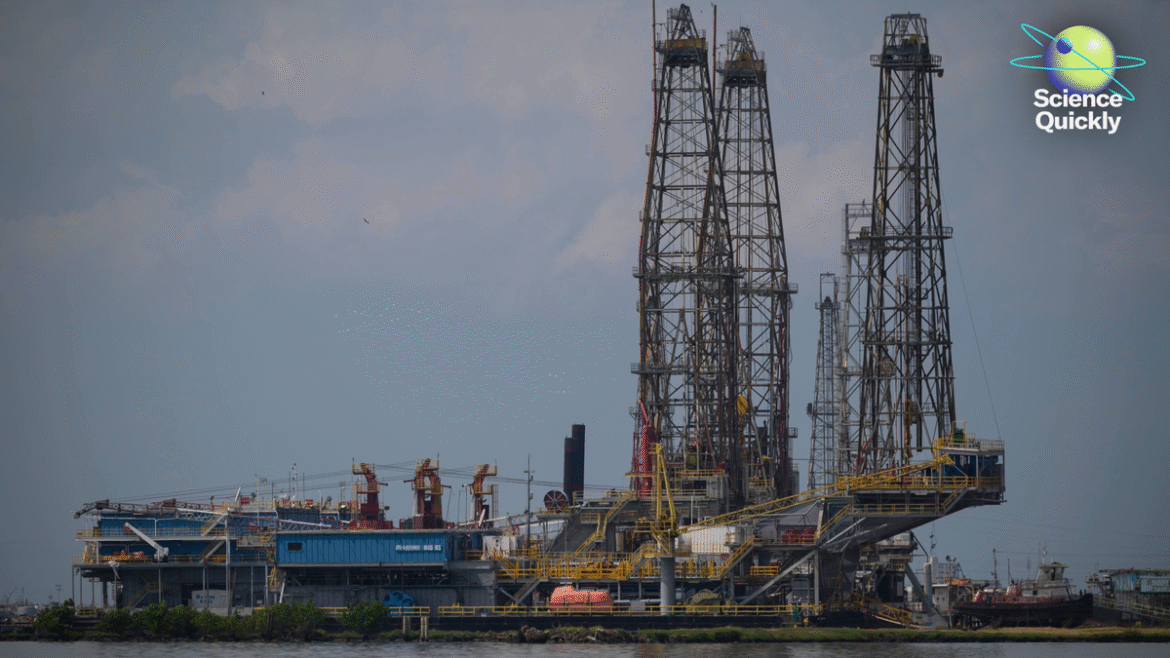

Over the past couple of weeks oil—specifically, Venezuelan oil—has been all over the headlines.

It started late on January 2, when President Donald Trump ordered U.S. military forces to enter Venezuela and capture the country’s president, Nicolás Maduro, which they did early the next morning. Last week the country’s interior minister said the action killed 100 people.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the intervening weeks President Trump has made clear that at least part of his motivation for the operation was the nation’s oil fields, which are home to an estimated 303 billion barrels of oil reserves, more oil than Saudi Arabia or any other country in the world.

To dig into the situation we spoke with Amy Westervelt, a climate reporter and executive editor of the multimedia climate reporting project Drilled. We talked to Amy about why Venezuela has so much oil, the history of the country’s oil industry and how this obsession with oil is impacting climate change.

Thank you for joining us.

Amy Westervelt: Thanks for having me.

Pierre-Louis: You perhaps know more about oil in South America than any other climate reporter I’ve met. What got you interested in it?

Westervelt: Actually, Guyana is what got me [Laughs] interested in it. So I got this press release from Exxon[Mobil] in, I wanna say, 2020 that said that Guyana was going to be their most productive basin within the next five to 10 years, that it would outpace even the Permian Basin in Texas. And I thought, “How did they go that big that fast?”

And then shortly after that I got some press releases from an attorney that had filed various cases in Guyana trying to stop the offshore project and arguing that part of the reason that they had moved so fast was that they had ignored various environmental regulations.

So those two things kind of came in the same week, and I thought, “Oh, this is really interesting, and I haven’t really seen much about it.” So I started working with a reporter in Guyana and then going back and forth myself to report on this, like, new oil industry that was being created in, you know, 2020.

Pierre-Louis: Okay, we will get back to Guyana, I promise.

Westervelt: [Laughs.]

Pierre-Louis: But before we get there …

Westervelt: Yeah.

Pierre-Louis: As you know the Trump administration recently invaded Venezuela and captured its president, Nicolás Maduro, under allegations of drug trafficking. Your recent article in Drilled mentions access to the region’s oil is a big motivator of what’s happening there. And kind of focusing primarily just on Venezuela for right now, Venezuela has a lot of oil, like, an estimated 303 billion barrels of oil, compared to the United States, which has roughly 46 billion barrels. A very basic question: Like, why does Venezuela and that area just have so much oil?

Westervelt: Well, they have the Orinoco Basin, which is the world’s largest oil reserve, basically [Laughs], so Venezuela has the most oil of anyone in the world. But it’s not great oil; it’s heavy crude. And so it’s kind of on par with, like, tar sands oil in Canada.

Pierre-Louis: So what does that mean? Because I think for most people …

Westervelt: Right.

Pierre-Louis: We don’t really think about, like, grade of oil. We don’t often see oil. If we have a vision of what oil is, it’s like The Beverly Hillbillies …

Westervelt: [Laughs.] Yes.

Pierre-Louis: And, like, it, like, trickling out of the ground. [Laughs.] So, so what do, like, grades of oil actually mean?

Westervelt: So the Venezuelan oil is heavy crude, which means it’s got a lot of stuff in it, which means that it is more expensive to refine, which cuts into oil companies’ margins. And it also is less favorable for a lot of different, like, types of engines, types of uses, which means that it gets a lower price on the market.

So as the price of oil has come down the price of heavy crude comes down even more because what we generally think of as, like, the price per barrel is sweet crude, you know? [Laughs.] It’s, like, it’s the good stuff. So whatever that’s at, which is lower, heavy crude is gonna be even lower than that. And then on top of that Venezuelan oil has had all these sanctions against it. Trump has been part of that, both in his first term and more recently.

So, you know—’cause I feel like the question is always like, “Why isn’t Venezuela Saudi Arabia, right [Laughs], like, if it has this much oil?” And there are a few reasons, one of which is, yeah, the quality of oil, the distance to markets for it and then the fact that it has sanctions on these markets.

More people are more interested in the stuff that doesn’t burn quite so heavy. Partly, that’s driven by environmental regulations as well.

But then on top of that they’ve known they had this oil for a long time. I mean, some people will say, like, the Spaniards knew it when they were colonizing Venezuela and all of that, but for sure they’ve been developing it since around World War I, when everyone was looking for more oil because that was the first kind of big fossil fueled war.

And American companies have been in there, like, pretty much since jump. So you have this weird thing that happens in a lot of situations where U.S. oil companies feel, like, this attachment to the oil industry there [Laughs] and this, like, entitlement to the oil that’s there as well.

But, like, Venezuela started trying to nationalize its oil industry in, like, the ’30s and ’40s. We found some documents from this old PR guy who got sent by Standard Oil to go try to, like, stop this from happening in the ’40s and was successful. And a big part of that was labor and, you know, the fact that workers were annoyed that, you know, they were being badly paid and badly treated by these foreign companies that were making so much money off of Venezuelan oil. So, you know, at that time, in the ’40s, it was all about kind of, like, dealing with the labor unions, getting rid of the labor unions, getting contracts in place that, you know, would prevent that from happening.

But they could only kind of stave it off for so long, and in 1976 Venezuela did nationalize oil, but they allowed a lot of joint partnerships, so it didn’t really overly affect U.S. oil companies [Laughs]—until [then-Venezuelan President Hugo] Chávez in 2007 said, “Okay, enough of this. Like, you can be here, but the majority shareholder in any oil project in Venezuela has to be the state oil company. And if you don’t like it, like, you can get out.” And both Exxon and ConocoPhillips refused.

And so they left, and he seized their assets. Chevron stayed as, like, a minority shareholder in some of the projects there, but that has been, you know, kind of up and down in recent years because of U.S. sanctions as well, so Chevron’s kind of been teetering. But when Exxon got kicked out they had this backup plan already in mind ’cause they had been camping out on an exploratory license in Guyana since the late ’90s.

Pierre-Louis: Yeah, and so my understanding is much of that infrastructure that Venezuela had is now quite old. And so just to summarize kind of the lay of the land: Venezuela has oil, but much of it is not that great, and it would need significant infrastructure investment to really get it pumping again to the degree that we seem to be talking about, and it wouldn’t necessarily command a great price.

Westervelt: To the tune of, like, tens of billions of dollars. Like, it’s not a small amount of money that we’re talking about here.

Pierre-Louis: And yet right across the border is Guyana, which has a ton of sweet, light crude. Can you talk about the conflict that has been playing out over the past few years between Venezuela and Guyana?

Westervelt: Yes, so that conflict actually goes back all the way to, like, the late 1800s. So Venezuela and Guyana have argued over this one area that’s called Essequibo. Venezuela has claimed that it’s a Venezuelan state for a long time. In the late 1890s—I think it’s 1899—there was an international arbitration ruling over this dispute that said, “No, this is where the border is. Essequibo is in Guyana.” And that, you know, was kind of fine for some period of time.

In the early ’60s this dispute kind of, like, came up again. Some people think, actually, it was around oil then as well ’cause there was some early exploration happening and some thinking that possibly there was oil off the coast there. And at that time there was another treaty that was signed that’s called the Geneva [Agreement], and it was signed by the U.K., Venezuela and British Guiana, which is what Guyana was at the time because it had not been given …

Pierre-Louis: Independence.

Westervelt: Independence yet, exactly. So it was signed, made official in 1966, and then just, actually, like, a few months later Guyana was just kind of added to it. Like, they were, like, made independent, so it’s like, “Oh, now it’s you guys,” but they never really, like, agreed to any of this stuff.

So in 2015 Exxon announced that they had found this enormous reserve of oil offshore Guyana. And immediately, Maduro started saying, “You know, actually, that’s Venezuela.” I talked to some petroleum engineers in Guyana, and some of them actually think that part of the reason Venezuela was concerned about the oil in Guyana was also that they think the reservoirs are connected, and so they were concerned that if the oil’s getting taken out, like, over here, it would reduce production in Venezuela as well.

But regardless, this whole dispute has flared up again since 2015. And in the last two years in particular Maduro started to get really aggressive about it. And this is the piece that I feel like has been missed by a lot of the coverage around Venezuela, is that, you know, he started sending, like, navy ships to, like, patrol around this area.

[Laughs.] In December of 2023 Maduro just, like, once again declared that Essequibo is a Venezuelan state. He had a referendum where the people of Venezuela voted, and, you know, the voting system in Venezuela has been under a lot of scrutiny for various reasons [Laughs] for a long time, but he claims that Venezuelan voters overwhelmingly agreed that this is part of Venezuela. And then in January 2025 he announced that they would be holding elections for the governor of this Venezuelan state.

As this is going on Guyana has now taken a claim to the International Court of Justice to ask them to rule on it. They’ve filed that claim in 2018. It’s been very slow-moving. But, like, the ruling has so far said, “Hey, you guys have to, like, keep the status quo until we make a final decision,” which hasn’t happened yet.

But then in March of 2025 Venezuela sent [naval ship] to Exxon’s floating offshore production vessel [Laughs] and told staff of that boat that they were in Venezuelan waters, you know, were, like, aggressively asking a bunch of questions. It was a very aggressive act, and it was directly at Exxon’s vessel, and that really got the U.S. involved. So all of a sudden both the U.S. State Department kind of issued a statement about it—there were, like, various entities that were saying, like, “Hey, you guys can’t do this. You need to calm it down.”

And then Marco Rubio actually went to Venezuela in late March of 2025 and gave this press conference with Guyanese officials, where he said, like, “Venezuela’s gonna have the U.S. military to deal with if it doesn’t calm it down with this stuff.”

Pierre-Louis: So undergirding all of this jockeying for oil is the fact that the planet is getting warmer …

Westervelt: [Laughs.] Right.

Pierre-Louis: Climate change is real …

Westervelt: Right, yeah, uh-huh.

Pierre-Louis: And the reality is that if we wanna maintain conditions that are suitable for human life, we need to stop using oil and fossil fuels altogether. It very much feels like we’re in [an] early 2000s redux, but the climate is much warmer. [Laughs.]

Westervelt: Yeah, it’s so much worse. I mean, this, actually, to me, was also what drew me to the Guyana story in the first place, is that [roughly] 90 percent of the population of Guyana is on this tiny sliver of coast right next to Georgetown that will be underwater in about 10 years.

Pierre-Louis: That’s shocking.

Westervelt: [Roughly] 90 percent of the population needs to move and yet they were going all in on this new oil industry. I was like, “What? What? Make it make sense.”

But the sad—to me, it’s, like, such an illustration of the total failure of the international community to do anything about this problem, to figure out, you know, any kind of climate damages or reparations policy. Because Guyana, which was also, like, the early poster child for paying developing countries for carbon sinks and working with the Global South on carbon credits and all of that stuff: like, they were—you know, Norway put a bunch of money into preserving forests in Guyana for the purpose of maintaining a carbon sink there. They’re one of the world’s largest carbon sinks still. They were like, “We can’t pay to move our entire country away [Laughs] from sea-level rise without this oil money.” So it is, like, the biggest “robbing Peter to pay Paul” story I have ever heard of, and it’s just—it’s mind-blowing that, like, they are now at the mercy of oil companies to pay for climate adaptation.

Pierre-Louis: That’s really tragic, if you think about it.

Westervelt: It’s totally tragic, yeah.

Pierre-Louis: From a climate perspective, what do you think is missing from the conversation around Venezuela and Guyana?

Westervelt: Well, I mean, I think the climate in its entirety is missing from that conversation. I feel like the fact that both of these countries are going to be massively hit by climate impacts is, like—it’s almost entirely missing. Even, you know, Guyana’s kind of saying, like, “Oh, well, you know, if we have all this oil money, then we can pay to, like, move everyone out of harm’s way.” Well, where is out of harm’s way?

What happens if there’s a blowout? Well, all of the Caribbean gets impacted by that. You have an oil spill that hits—I mean, Exxon’s own environmental impact report on this shows that if such a thing were to happen, it would impact 14 different Caribbean countries, 14, and all of which are at least somewhat dependent on tourism …

Pierre-Louis: Mm-hmm.

Westervelt: For their economy, so once those beaches are destroyed by an oil spill, how’s that gonna go? Not to mention, like, food source …

Pierre-Louis: Yeah, fishing …

Westervelt: [Laughs.] Fishing.

Pierre-Louis: Is big in the Caribbean.

Westervelt: Exactly. So there’s so many layers of problems here.

And again, I just feel like—when I talked to people in Guyana, too, about, “What’s going on here? Aren’t you guys—I thought you guys were so concerned about the environment [Laughs] and climate and whatever,” they’re like, “Yeah, we are, but, like, how are we gonna pay for all of this stuff?” And they were, like, a little bit—and I don’t think they’re wrong in this—“Well, what’s the difference between taking money from the Norwegian government to keep our trees [and] taking money from Exxon to drill our oil?”

Pierre-Louis: Right, well, this has been—I won’t say a lovely conversation, but it has been …

Westervelt: [Laughs.]

Pierre-Louis: [Laughs.] An illuminating conversation …

Westervelt: Yeah.

Pierre-Louis: Thank you so much for your time today.

Westervelt: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Pierre-Louis: That’s all for today. Tune in on Monday for our weekly science news roundup.

But I have a favor to ask before you go. I need your help for a future episode—it’s about kissing. Tell us about your most memorable kiss. What made it special? How did it feel? Record a voice memo on your phone or computer and send it over to ScienceQuickly@sciam.com. Be sure to include your name and where you’re from.

Science Quickly is produced by me, Kendra Pierre-Louis, along with Fonda Mwangi, Sushmita Pathak and Jeff DelViscio. This episode was edited by Alex Sugiura. Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck fact-check our show. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Subscribe to Scientific American for more up-to-date and in-depth science news.

For Scientific American, this is Kendra Pierre-Louis. Have a great weekend!