December 18, 2023

3 min read

The James Webb Space Telescope caught its second glimpse of the year of Uranus and its bright-shining rings

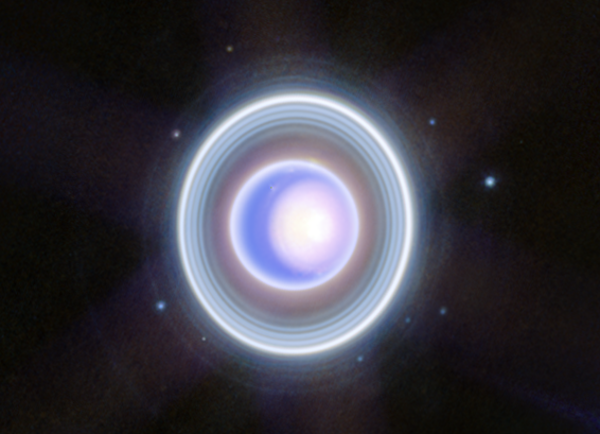

This image of Uranus from NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) on the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope shows the planet and its rings in new clarity. The Webb image exquisitely captures Uranus’s seasonal north polar cap, including the bright, white, inner cap and the dark lane in the bottom of the polar cap. Uranus’ dim inner and outer rings are also visible in this image, including the elusive Zeta ring — the extremely faint and diffuse ring closest to the planet.

They may not be the gold rings from “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” but Uranus and its rings stand resplendent in this stunning portrait from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

It’s the second image of Uranus that the JWST has captured this year. The first, released in April, was a two-toned affair composed of imagery captured at infrared wavelengths of 1.4 and 3.0 microns. This new image adds extra wavelengths, specifically 2.1 and 4.6 microns, to give a much more complete overview of the seventh planet from the sun.

The new JWST Uranus image doesn’t just show the planet, however. Uranus’ aforementioned rings shine bright in infrared light, and the JWST’s optics have even resolved the elusive, diffuse inner Zeta-ring. Many of Uranus’ 27 moons are also on display; the cropped view shows some of Uranus’ smaller, fainter moons including some embedded within the rings, while the wider view shows Uranus’ five large moons: Ariel, Miranda, Oberon, Titania and Umbriel.

The extra wealth of detail in these new images places Uranus’ north polar cap in the spotlight. Unlike Earth and Mars‘ polar caps that are made from solid ice, Uranus is a gaseous world and its polar caps are hazy haloes of aerosols that hang high in its atmosphere.

The JWST’s new image shows Uranus’ north polar cap almost directly facing us (and therefore also facing the sun), with a bright spot at its center and a dark collar, both of which have previously been seen in infrared and radio-wavelength observations, but never with this clarity before. The bright spot, seen as white in the new JWST, is warmer than its surroundings and is the center of a huge cyclonic vortex.

Bright storms are also visible blowing their way around the polar cap, and are believed to be at least partially caused by seasonal variations. Uranus is a really odd planet, in that for reasons unknown it rolls around the sun on its side, tilted by 98 degrees to the plane of the ecliptic (the plane of the orbits of the other planets). Rather than its poles being ‘on top’ of the planet, we see them head-on, and this brings with it unique climatic conditions that astronomers are eager to witness with the JWST in the run up to Uranus’ northern summer solstice in 2028.

It is at the solstice that the weather in the planet’s polar cap becomes most active. Uranus’ tilt means that for about a quarter of a Uranian year, which is 84 Earth-years long, one pole is in constant daylight and the other in enduring night. Right now the north pole is facing us, but in 2070 it will be the turn of Uranus’ southern pole to bask in what passes for summer at such a great distance from the sun (2.96 billion kilometers/1.83 billion miles).

It seems strange now to think that back in 1986 when NASA’s Voyager 2 mission flew past the ice giant, the general consensus was that blue–green Uranus appeared a bit boring, with a bland atmosphere that was a let down after the smorgasbord of atmospheric tumult seen on Jupiter and Saturn. Little did planetary scientists realize that at infrared wavelengths, which allow us to view beneath the featureless haze, Uranus has a lot going on, as the JWST’s advanced vision shows.

Besides providing the best data yet for planetary scientists trying to figure out how Uranus’ atmosphere works, the observations will also prove vital in honing the scientific questions to be asked by a future mission to Uranus.

The recent Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey highlighted a mission to Uranus as its number one priority. Orbital alignments mean that a mission, which will take over a decade to reach Uranus, will need to launch by 2030; planetary scientists are still nervously awaiting the go-ahead from NASA.

Until that time, we’ll just have to settle for the remarkable images that the JWST has to offer.

Copyright 2023 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.