One of the most iconic paintings to depict the horrors of war is Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808, which depicts an incident during the Peninsular War against Napoleon in Spain.The nighttime scene of a group of Spanish civilians facing execution by a French firing squad was remarkable for its time, being utterly devoid of the patriotic glorification of war that characterized most contemporary war art. Goya based the painting on reprisals the French army carried out against citizens of Madrid in the wake of the Dos de Mayo Uprising against Napoleon’s occupation forces.

When French troops were attacked by supporters of the deposed Spanish royal family, the French commander Marshal Joachim Murat posted broadsides around the city proclaiming: “The population of Madrid, led astray, has given itself to revolt and murder. French blood has flowed. It demands vengeance. All those arrested in the uprising, arms in hand, will be shot.” Because “arms in hand” was interpreted to mean any person found with scissors, pocketknives, or shears, numerous innocent civilians were summarily shot without trial in the roundups that the French carried out in reprisal after the uprising. As many as 700 Spanish citizens were killed in the revolt and its aftermath.

Vengeance in War

Military reprisals against civilian populations have occurred throughout thousands of years of recorded history. Genghis Khan’s Mongols are said to have massacred the entire population of the Persian city of Nishapur in 1221 in reprisal for the killing of the Khan’s son-in-law during the siege. The death toll, according to contemporary chroniclers, may have been more than 1.5 million men, women, and children.

During the Peasants’ Revolt against Egyptian conscription policies in Palestine in 1834, Egyptian troops committed mass rapes and killed nearly 500 civilians when they captured the town of Hebron in their campaign to put down the uprising. When imperial Qing forces recaptured Guangdong province during the Taiping Rebellion in 1853, they massacred nearly 30,000 civilians a day. According to some histories, the total death toll from unrestrained reprisals in that province alone amounted to approximately a million people.

After the Prussian army invaded France during the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, territory under Prussian occupation quickly felt the harsh hand of military rule, and reprisals against the local population were part of the Germanic policy of military domination. When the regular formations of the French army went down in defeat, local citizen militias organized as francs-tireurs initiated a low-intensity guerrilla war against Prussian forces. In retaliation, the Prussians not only summarily executed any captured francs-tireurs, but also rounded up and executed numbers of civilians unfortunate enough to reside in the vicinity of those attacks.

20th Century Conflicts

With this experience in mind, at the onset of the First World War the German army was predisposed to harsh treatment of civilians in its area of operations. In 1914, German infantry burned the Belgian town of Leuven and shot 250 civilians of all ages in retaliation for attacks on German soldiers. Hundreds more Belgian citizens in the towns of Dinant, Tamines, Aarschot, and Andenne were killed in of the reprisals.

In military history of the 20th century, Nazi reprisal operations against civilians during the Second World War are frequently cited as extreme examples of reprisal as a war crime, to the point that the very word “reprisal” is almost inextricably linked to the German military in that conflict. However, it remains an undeniable fact that even nations usually regarded as being outspoken champions of lawful warfare have stubbornly resisted the idea of completely giving up the option of carrying out reprisals, even if they did not often resort to such action in practice.

Reprisal was long regarded as an indispensable weapon in the arsenal of a nation’s ability to wage and win wars; near universal condemnation of military reprisals as a legitimate tactic is a relatively recent development in international laws of war. Looking back at Nazi war crimes during the Second World War, it is important to distinguish between the types of war crimes. The Nazi effort to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population was perhaps the most horrific example of state-sponsored genocide. On the other hand, Nazi policies such as the Commissar Order of June 6, 1941, and the Commando Order issued a year later on Oct. 18, 1942, both ordered the summary execution of all enemy combatants of certain specific type and were criminal under international laws of war because they were illegal orders. When it came to reprisals, the German military took a longstanding concept of warfare accepted by most nations and transformed it into something that far transgressed the original idea of mutual restraint articulated in extant laws of war. The way in which German forces conducted military reprisals graphically illustrate the danger that faced any nation that clung to the idea that reprisal was a legitimate tactic of war.

Defining War Crimes

The reasons why reprisals continued to be defended in laws of war as long as they did, even if most nations were careful to describe them as a measure of last resort, was because they were believed to be necessary in two particular tactical situations: to respond to an enemy’s violation of the laws of war, a response in kind in order to force one’s foe back into lawful belligerency; and to retaliate against an elusive, irregular enemy who could not otherwise be engaged by conventional means of combat.

These were exactly the arguments made in both American and British concepts of laws of war well into the 20th century. As the American Rules of Land Warfare on the eve of the Second World War stated “…commanding officers must assume responsibility for retaliative measures when an unscrupulous enemy leaves no other recourse against the repetition of barbarous outrages.” The British Manual of Military Law of the same era declared that reprisals “are by custom admissible as an indispensable means of securing legitimate warfare.”

What neither code stipulated, however, was any measure of proportionate response. As the German military demonstrated all too often between 1939 and 1945, any doctrine that allowed reprisal without explicitly linking its implementation to limited, proportionate response was a recipe for the worst kinds of atrocity. In 1948 the United Nations War Crimes Commission suggested that one reason why the Second World War saw such flagrant violations of previously existing laws of war was perhaps because “the institution of reprisals which, though designed to ensure the observance of rules of war, have systematically been used as a convenient cloak for disregarding the laws of war…” That accurately described the German use of reprisals during the Second World War. Almost immediately from the beginning of Nazi occupation of conquered territories during the war, it was clear that reasonable restraint and proportionate response would be completely ignored. In German reprisal operations, regardless of whether the action was carried out by the SS or Wehrmacht units, restraint was never in evidence.

When French Resistance operatives assassinated a German naval cadet in Paris in 1941, Nazi occupational authorities put up posters all over the city declaring an official policy stating that 10 French citizens would be executed for every German soldier killed. Even that arbitrary limit was meaningless, because when a senior German officer was killed a short time later, the Germans seized 50 French civilians at random and shot them all, warning that if the assassins were not identified another 50 Frenchmen would be executed. When the deadline passed, the Germans shot another 50 civilians. In that instance, regardless of the stated reprisal policy of ten to one, the ratio of lives destroyed was 100 to one, each an innocent civilian who had no connection to the act that precipitated the reprisal.

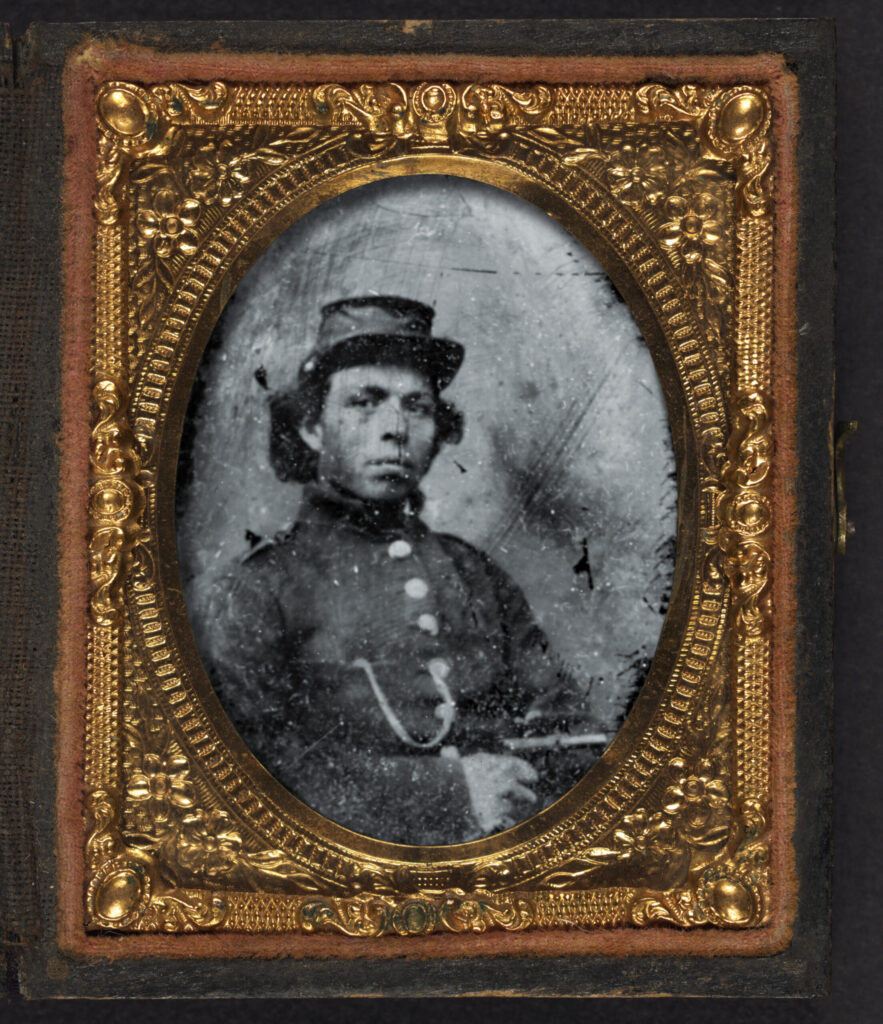

(Library of Congress)

Reprisal on the notional scale of 10 to one occurred in other Third Reich reprisals. The same calculation was used after a partisan bomb in Rome on March 23, 1944 killed thirty-two people, most of them members of the SS Police Regiment Bozen. The local German commander, Luftwaffe Generalmajor Kurt Mälzer, ordered that 330 Italians were to be executed in reprisal for the attack, a number that represented 10 victims for every person killed in the bombing (even though five people killed in the incident were themselves Italian civilians). The day after the partisan attack, in an incident remembered as the Ardeatine Massacre, 335 Italian citizens were shot in groups of five by SS officers in the Ardeatine Caves outside Rome. The youngest victim was 15; the oldest was 74. The disparity between Mälzer’s chosen number and the additional five people murdered in the operation was because when five prisoners in excess of the expected count were mistakenly delivered to the massacre site, the Germans simply shot them along with the others.

The International Military Tribunal

In an earlier incident that underscored the degree to which the German military could disregard even notional concepts of proportionality, the Germans perpetrated a more savage act of reprisal at Kragujevac, Serbia, in October 1941. After a partisan attack killed 10 German soldiers and wounded 26 others, soldiers of the 717th Infantry Division summarily shot 300 random civilians. Over the following five days a district-wide retaliation resulted in the executions of another 1,755 people, including 19 women. This brutality was possibly prompted by the issuance of the “Communist Armed Resistance Movements in the Occupied Areas” decree, signed a month earlier by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel, head of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces, who was later tried for war crimes by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. That order specified that on the Eastern Front, 100 hostages were to be shot for every German soldier killed and 50 were to be shot for every soldier wounded. The resulting Kragujevac massacre caused the deaths of nearly 2,800 Serbs, Macedonians, Slovenes, Romani, Jews, and Muslims. When the initial roundup of hostages did not turn up enough adult males, 144 high school students were seized and shot. German troops had carried out reprisals in earlier wars, but never occured on such a homicidal scale as under the Nazi regime. After 1914 the German word “Schrecklichkeit,” which can be understood as “terror,” entered the lexicon to describe these actions against civilians. The massacres of Lidice in Czechoslovakia, Oradour-sur-Glane and Maillé in France, Wola in Poland, and Sant’Anna di Stazzema in Italy, are only five on a long list of atrocities the Nazis carried out in the name of military reprisals.

The International Military Tribunal and other war crimes tribunals that took place following the Second World War represented a seismic shift in how reprisals were considered under international laws of war. Reprisal continued as an option in lawful warfare, but in much more carefully delineated form. As the Practical Guide to Humanitarian Law explains, “It is important to distinguish between reprisals, acts of revenge, and retaliation. Acts of revenge are never authorized under international law, while retaliation and reprisals are foreseen by humanitarian law.”

The essential distinction in that statement is that reprisals against civilians are now considered to be in the nature of revenge, and therefore never legal. “In times of conflict,” as current legal opinion holds, “reprisals are considered legal under certain conditions: they must be carried out in response to a previous attack, they must be proportionate to that attack, and they must be aimed only at combatants and military objectives.” Limited reprisals against soldiers, however, still remain in the realm of extreme possibility.

The U.S. Civil War

This is not a new idea. During the American Civil War, when the Confederate States threatened to not treat captured Union soldiers as legitimate combatants if they happened to be Black men, the United States issued the Retaliation Order of 1863. “The government of the United States will give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave anyone because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy’s prisoners in our possession,” the Order stated. “It is therefore ordered that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war.” The fact that the Retaliation Order specifically provided for reprisals against enemy prisoners, rather than enemy soldiers on the field of combat, is the only part of that order that would violate modern restrictions on military-vs.-military reprisals.

The U.S. Civil War was also the conflict during which the German American jurist Franz Lieber transformed American military law with his revolutionary work General Order 100. As Article 27 of Lieber’s Code stated, “The law of war can no more wholly dispense with retaliation than can the law of nations, of which it is a branch. Yet civilized nations acknowledge retaliation as the sternest feature of war. A reckless enemy often leaves to his opponent no other means of securing himself against the repetition of barbarous outrage.” The point of Lieber’s position was that retaliation was sometimes necessary to prevent greater violations of lawful warfare, but also that careful restraint was indispensable. “Unnecessary or revengeful destruction of life is not lawful,” Article 68 stated, a declaration that 80 years later could have been applied to Nazi practices of military reprisals. In the interim, the U.S. Army used General Order 100 to justify reprisals on the Island of Samar during the Philippine-American War. Brig. Gen. Jacob Smith ordered his troops to “kill everyone over the age of ten [and make the island] a howling wilderness.”

Civilians and International Laws

A detailed examination of military history shows that reprisals against civilians always exacerbates conflict and heightens resistance rather than eliminating it. The German military never managed to stamp out resistance to its occupation forces during WWII, no matter how savage the reprisals it unleashed against civilian populations. Reprisals also present the risk of an unending cycle of violence as each opposing side responds to the hostile acts. In the words of the U.S. Naval Handbook, “there is always a risk that [reprisal] will trigger retaliatory escalation (counter-reprisals) by the enemy. The United States has historically been reluctant to resort to reprisal for just this reason.”

Of course, reluctance to engage in an act is not nearly the same thing as an outright policy prohibiting it. As the International Committee of the Red Cross observes, although “favour of a specific ban on the use of reprisals against all civilians is widespread and representative, it is not yet uniform.” Even today, with all of the advances in international conventions on lawful warfare, the United States and Great Britain still have not unreservedly committed themselves to a total ban on the use of reprisals in war.

The United States “has indicated on several occasions that it does not accept such a total ban, even though it voted in favour of Article 51 of Additional Protocol I and ratified Protocol II to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons without making a reservation to the prohibition on reprisals against civilians contained therein.” Great Britain, for its part, “made a reservation to Article 51 which reproduces a list of stringent conditions for resorting to reprisals against an adversary’s civilians.” Both nations have preferred to hedge their bets and retain the option of a military tactic they might use only in the extreme but are not willing to completely forego.

Current conventions on international laws of war have made great strides in restricting the use of reprisals in war but have never succeeded in eliminating it in practice. It is doubtful that the practice will ever completely disappear from the world’s battlefields, though it is to be hoped that such actions will increasingly be regarded as war crimes rather than legitimate combat.