So you’ve had a “fender bender” in your plane and are in need of some wings. What do you do?

You could rent a plane from the local flight school. But at a cost of $155 per hour (whether the propeller is turning or not) that is simply not practical. Can you borrow a plane? Perhaps, but after someone learns why your plane is in the shop they might not be so keen on handing over the keys to their bird. You could bum rides from friends. Sure, but they may not stay friends for long. Or you could give up flying until your plane is repaired and use the time to work on your golf game. Never!

That leaves just one option: Buy a second plane.

The challenge is that planes are notoriously poor investments—in most cases they are either way overpriced or in such poor condition that the cost of making them airworthy makes them unaffordable. Finding a plane you can both afford and actually fly as soon as you’re handed the keys takes some luck, and a strategy.

I wanted a basic machine, nothing fancy—a simple Cessna or Piper—something for day trips to the islands or Cape. It didn’t need to go fast. It didn’t need to be all-weather. It just needed to be reliable.

So my search began where all searches begin: the internet. But like all internet searches, frustration quickly set in. My search ran up against the reality that lots of people are looking for the same plane, particularly flight schools and new owners. Such planes, being in high demand, command a hefty premium in price. Not only that, but such planes also tend to be very high time (read: worn out), and thus more trouble than they’re worth.

I needed to change my approach. After a couple of dead ends, I found an area of aviation where one can still find a simple, affordable aircraft: Vintage planes. The plane I generally fly is 60 years old, so by vintage I mean planes that are really old, almost antique. These are planes built not long after the dawn of aviation; planes that are covered in cloth rather than metal; planes manufactured by companies long out of business…the Taylorcrafts, the Luscombes, the Aeroncas, the Stinsons and the Swifts.

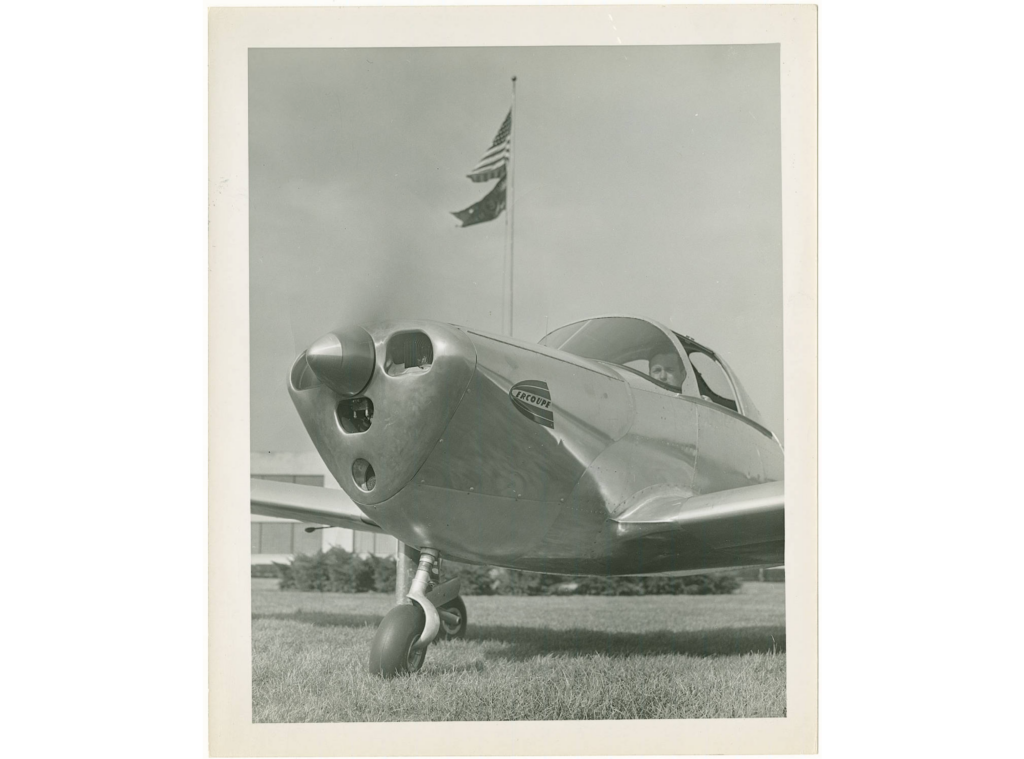

And what I landed upon surprised me: the Ercoupe, a twin-tail, tricycle gear, metal and cloth hybrid that was way ahead of its time when it was designed in the mid-1930s. Back then, the Ercoupe seemed poised to do for aviation what the Model T did for the automobile.

(Courtesy College Park Aviation Museum)

In 1935, less than a decade after Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis, aviation had—to use a bad pun—taken off. Airline traffic in the United States was doubling every year, carrying more than 900,000 passengers (compared to more than 853 million passengers per year today). Each year saw a proliferation of new airlines, new airplane manufacturers, new records being made or broken and exploding interest in aviation.

In all this heady optimism, the Department of Commerce sought to bring airplane ownership within reach of ordinary citizens. Under the auspices of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the forerunner of NASA, it challenged engineers to develop a machine that inexperienced pilots could operate, at a price much less than conventional airplanes.

From this emerged the Ercoupe, a name derived by the name of the company that produced it, Engineering and Research Corporation (ERCO). Designed by legendary aeronautical engineer Fred Weick, the Ercoupe incorporated a number of features that made the plane simpler and safer to fly. This included tricycle landing gear, which made the plane much easier to take off and land than its tail-dragging cousins. The plane’s twin tails were designed to be outside the propeller wash, which alleviated unwanted yaw movements on takeoff and at slow speeds. The bubble canopy gave the pilot unmatched visibility. The fuel-air mixture was fixed, so there was no mixture control. There were no flaps. Elevator deflection was limited, making stalls nearly impossible. And, most importantly, the plane’s flight controls were integrated—the rudders were linked to the ailerons. That meant no rudder pedals, which also meant all turns were coordinated. Because of this, the Ercoupe was the first plane to be certified as “characteristically incapable of spinning,” and every plane has a placard on the control panel stating as much. On the ground, the nose-wheel was also linked to the control yoke, so the plane steered like a car.

(Courtesy College Park Aviation Museum)

ERCO marketed the Ercoupe as “the world’s safest plane,” one as easy to operate as the family car. In 1945, the sticker price was $2,665. A Buick sedan, by comparison, sold for $1995. In another first, you could buy an Ercoupe in a department store. Macy’s took out a full-page ad in The New York Times in 1945 to herald the opening of its airplane department. At Hamburger’s in Newark, New Jersey, elevator operators hollered, “Sixth floor, airplanes!” Aviation was going retail.

But the dream of “an airplane in every garage” never materialized. Though safer and easier to fly than conventional planes, the reality is that the Ercoupe still requires airmanship—not to mention a license—to fly. And that includes knowledge of weather, aviation regulations, navigation and aeronautics. The average American wasn’t quite ready for this. Sales stalled. In 1950, ERCO sold the rights to the Ercoupe to the Forney Aircraft Company. Fred Weick moved on to Piper Aircraft, where he later designed the venerable Piper Cherokee, one of the most popular airplanes of all time. A succession of companies made Ercoupes up until 1967—a total of 5,685 in all—an exceptionally long run for a general aviation aircraft. Of those, more than 2,000 are estimated to still be flying.

A well-maintained Ercoupe still costs less than a compact sedan. The plane I found was born in 1946. When I first laid eyes on it, I thought it looked like an MG with wings. It was painted in the silver-and-yellow WWII Army Air Corps trainer scheme. Very sharp.

(Tom LeCompte)

Thing is, the only Ercoupes to actually serve in the military were a pair bought by the Army in 1941 that were evaluated for use in observation and later used as target drones. The government used another Ercoupe to test jet-assisted take-off (JATO), in which a short-burst rocket was strapped to the fuselage for a high-powered take-off.

So the plane’s military paint scheme was a bit of a fraud, but that’s okay because—having never served in the military—so am I. After getting it home, I placed a series of mosquito stickers along the side of the plane that attest to my “confirmed kills.”

(Tom LeCompte)

The man who sold it to me is a Navy veteran and retired Boeing 747 captain. He told me Pan Am used the Ercoupe to train its early crews in how to land in a crab. The conventional technique of banking the plane and applying opposite rudder to stay on the runway centerline wouldn’t work with the giant 747 because the outboard engines could scrape the pavement if the wings weren’t level.

“The technique was to fly in the crab, and at 50 feet above the runway the flight engineer would call ‘50 feet’ reading the radar altimeter and the pilot would bring the nose around with rudder to straighten it out and reduce side loads on the main gear,” he told me. “Worked well! Thank you Ercoupe for the help!”

My insurance company required me to get an instructor’s sign-off before covering me for solo flight. My instructor, a young guy who flies for a major airline, had never heard of an Ercoupe. When I told him it had no rudder pedals, he sounded perplexed. “How do you land it?” he asked. “We’ll figure it out,” I said.

The plane, we discovered, is an absolute cinch to fly. Flip the battery switch, turn on the magnetos and just pull the starter. With the carburetor wired, there’s no fuel mixture to adjust. Gas from the plane’s two wing tanks is gravity fed to the engine, so there’s no tank selector. Just “drive” the plane out to the runway, line it up, push in the throttle and when the plane hits 65 miles per hour lift it off the runway.

You’re not going to go very far or go very fast with a cruising speed of around 95 miles per hour. And if there’s a stiff headwind you may find that cars on the highway below are passing you. But with the windows down and the wind in your hair you get the feeling that this is the way flying was meant to be…that “slipped the surly bonds of earth” sort of thing. More than anything, it is just fun.

Want to check out some basic aeronautics? Stick your arm out the window and hold it in the wind. Watch the nose drop and the plane begin to turn (this is actually an approved technique for making a rapid descent). Put the plane into a steep turn and you’ll get the feeling there’s nothing between you and the ground. Circle over Gillette Stadium and it will be like you’re on a string spinning over it.

But the best part of it is bringing it home. Given all my experience and training, I thought that landing sideways onto the runway would make for a hair-raising, jarring arrival. Not so. The trailing-link gear gently cushions the landing and the plane naturally pivots in the direction of flight, straightening out for a smooth, effortless landing.

“How can you tell when you’re on the ground?” my brother asked when I took him up for a flight.

I wish all my landings could be like that.

Tom LeCompte is a freelance writer, airplane owner and longtime pilot based south of Boston. When not writing or researching stories, he’s airborne somewhere. This article originally appeared on his blog, nineronepop.blogspot.com.