The Curtiss-Wright Corporation came into being in 1929 through the merger of companies started by pioneering aviators Glenn Curtiss and the Wright brothers. Within the new company, the Curtiss-Wright airplane division made airplanes while the Wright Aeronautical Corporation focused on engines. By the time of World War II, Curtiss-Wright held more defense contracts than any organization other than vastly larger General Motors and had become something of a bully. It used lobbyists, legislators, friends in high places and its own overzealous salesmen to get what it wanted. It made some adequate but unspectacular airplanes and some big radial engines, but why Curtiss-Wright could punch so far above its weight remains something of a mystery.

Trouble arrived for Curtiss-Wright in 1943 when its engines became the focus of a congressional investigation led by a senator named Harry S. Truman. The inquiry, launched back in March 1941, was formally known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program and it helped propel the obscure politician from Missouri into the vice presidency and eventually the White House. Strangely enough, it also impacted the life of actress Marilyn Monroe—but more about that later.

At the time, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk was the company’s go-to product. The design was essentially a 1933 radial-engine Curtiss P-36 Hawk fitted with an inline Allison V-12 engine. While not a bad airplane, the P-40 was obsolete by the time the United States entered World War II. Still, it was the best America had at the time. Messerschmitt Me-109s and Mitsubishi A6M Zeros ran rings around it at altitude—the P-40 had just a single-stage supercharger—but it remained an effective ground-attack machine.

Yet the obsolete P-40 stayed in full production until the end of 1944. Why not ramp up manufacture of the North American P-51 Mustang and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt instead, Truman’s investigative committee asked? But Curtiss liked the easy profit it derived from the simple, proven, utilitarian design, and its attempts to create a successor—the XP-46, XP-60 and XP-62—were uninspired. All were canceled. Curtiss had no aeronautical geniuses like Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson, North American’s Ed Schmued or Republic’s Alexander Kartveli to push it to the forefront. Its best talent was an engineer named Don Berlin, who was held in high regard but never really rose beyond his singular success with the P-40. It is notable that when the British asked North American Aviation to license-build P-40s for the Royal Air Force, the California company said, “Hell, give us three months and the back of an envelope and we’ll design a real fighter for you.” That fighter became the Mustang.

(Library of Congress)

One new airplane the company had to offer was the SB2C Curtiss Helldiver, but it was an ill-handling, poorly manufactured, aerodynamically misshapen beast loathed by pilots, back seaters and maintainers. It was not a Don Berlin design but was credited to Curtiss engineer Raymond C. Blaylock, who seemed to have stepped out of obscurity long enough to head the Helldiver program and then disappear. (In fact, he ultimately became the vice-president of engineering of Chance Vought. He specialized in missiles and was not involved in the design of the remarkable F8 Crusader.)

To be fair, it wasn’t all Curtiss’s fault. The Navy ordered the SB2C to succeed the Douglas SBD and demanded that a pair of the Curtiss dive bombers had to fit on a fleet carrier’s elevators while at the same time requiring that the SB2C be faster and longer-ranged than the SBD and carry a heavier load of ordnance. This led to the Helldiver receiving an awkwardly short aft fuselage, a huge vertical tail that nonetheless failed to keep the short-coupled airplane longitudinally stable, and a monster wing to lift all that weight at carrier-approach speeds. When Curtiss put a prototype SB2C model into the MIT wind tunnel in 1939, aerodynamicist Otto Koppen said, “If they built more than one of these, they are crazy.”

The Helldiver’s poor handling characteristics, structural weaknesses—it tended to shed the aft fuselage and empennage under the stress of arrested carrier landings—and lousy stall characteristics at final-approach speeds caught the Truman Committee’s attention. It didn’t help that Helldiver production had been delayed by nine months while the Navy demanded more than 800 modifications. For many months thereafter, Curtiss failed to produce a single SB2C that the Navy considered usable as a combat aircraft. What particularly griped the Truman Committee was that Curtiss had been spending tens of thousands of government dollars advertising the SB2C to the public as “the world’s deadliest dive bomber,” despite the fact that it had not produced a single usable Helldiver.

There was even a song about the SB2C. It went, “Oh mother, dear mother/Take down the blue star/Replace it with one that is gold/Your son is a Helldiver driver/He’ll never be 30 years old.” The Australians and the British were smart enough to cancel their large orders for the SB2C before more than a few were built.

Initially, Curtiss was to construct the SB2C at a huge new government-funded factory in Buffalo, New York. Then production was shifted to Columbus, Ohio. For months, nothing happened, and rumors began circulating among the sidelined workers in Columbus that their efforts were being literally sabotaged. Nobody realized that the problem was the fact that Curtiss hadn’t been able to produce a single successful airplane in Buffalo.

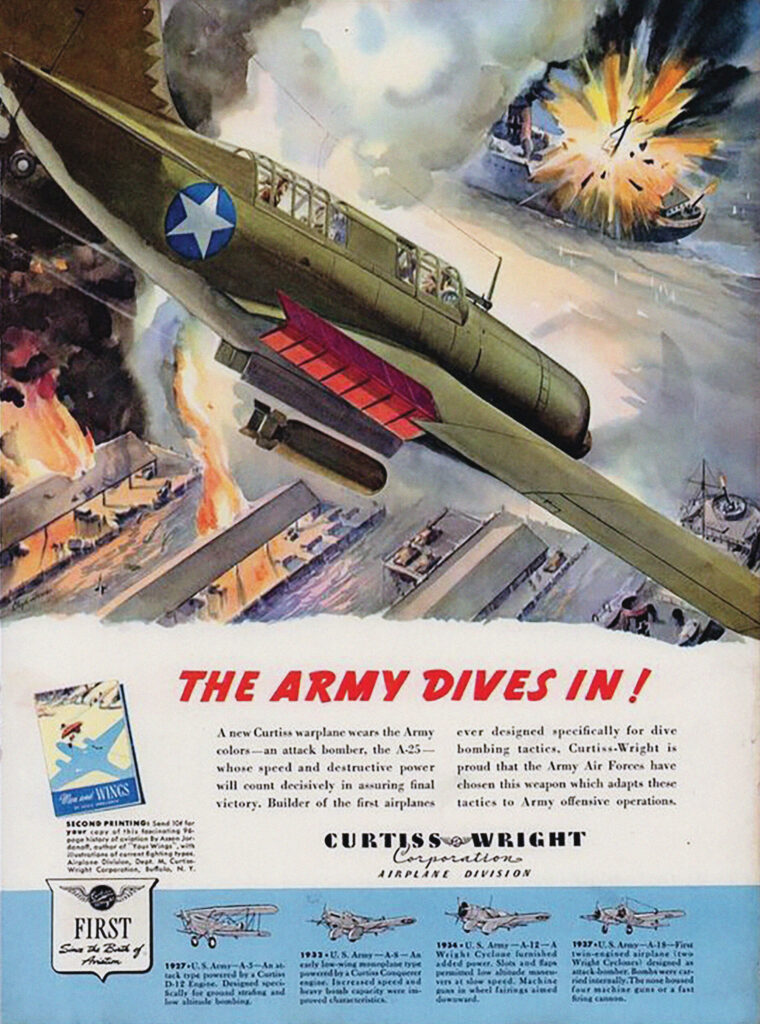

Nevertheless, the U.S. Army Air Forces (AAF) ordered thousands of Helldivers as a variant called the A-25 Shrike dive bomber. Big mistake. The Germans had already learned, with the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, that terrestrial dive bombing worked only if the bombers had total air superiority and were attacking targets undefended by anti-aircraft guns. That kind of situation was rare enough that Allied air forces had abandoned the concept of dedicated dive bombers by the time the A-25 was ready for delivery.

(HistoryNet Archives)

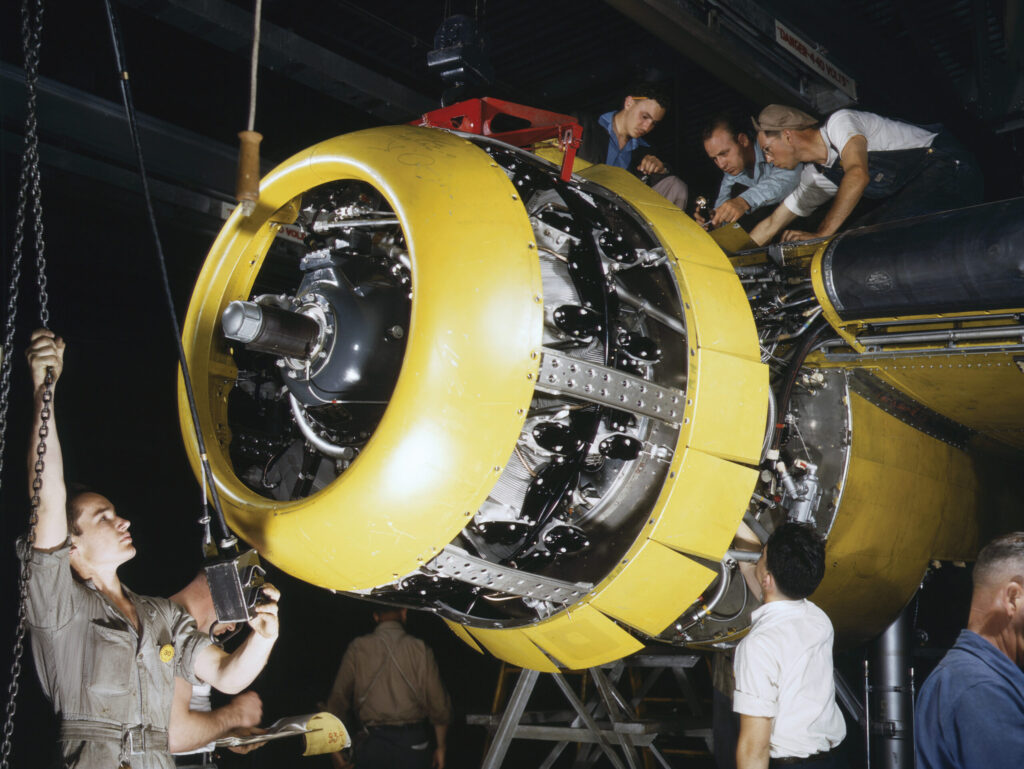

Things were bad enough with Curtiss airplanes. They were even worse for the engines being produced by the Wright Aeronautical Corporation. Several Army inspectors stationed at Wright’s engine factory at Lockland, Ohio, told Truman that they were being encouraged to ignore proper inspection procedures and to approve faulty materials and even entire engines being delivered to the government for use in the Helldiver and various other aircraft. That engine was the 1,600-hp Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone.

The R-2600 was the engine that goaded Pratt & Whitney into designing and producing the R-2800, the best radial of World War II, but the big Wright was an excellent engine itself—when it was built right. It powered thousands of North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, including those that flew America’s first offensive strike against Japan—the April 1942 Doolittle Raid.

A preliminary investigation by Truman’s staff revealed that there were ample grounds for the whistleblowers’ claims, and that the inspection failings were obvious enough that company execs and Army inspectors should have been aware of the problems.

Well, let’s not be hasty here, the Army said. We’ll look into this and report back. Brig. Gen. Bennett Meyers and his staff did so, and Meyers announced that the Army could find nothing amiss. Meyers either lied or had been duped by his own inspectors, whom the Truman Committee later found to be actively obstructing the investigation.

The engine division blamed the snitching on “petty bickering over privileges, authority and rights.” The Truman Committee, however, soon uncovered evidence of false tests of R-2600s and the materials that went into them, destruction of records, improper reporting of test results, forged inspection reports, off-the-cuff oral alteration of the tolerances allowed for parts, outright skipping of inspections and, in general, letting Wright’s engine-production needs override the recommendations of both company and Army inspectors.

There almost certainly had been crashes and deaths caused by the failure of faulty Wright R-2600s, but nobody could identify any specific examples outside the mass of wartime catastrophes attributable to everything from thunderstorms to pilot error. Truman himself said, “The facts are that [Wright was] turning out phony engines, and I have no doubt that a lot of kids in training planes were killed as a result.” The fact that no 1,600-hp Wright Twin Cyclone had ever powered a trainer escaped his attention, but never mind.

(Hulton Archive/Getty Images;

)

As is often the case in such relationships, a culture had grown that encouraged Army inspectors to believe their primary duty was toward Wright rather than the AAF, and that keeping their jobs depended on keeping the company happy. If an Army inspector refused to accept material that he knew was faulty, he got a reputation as a knucklehead who failed to “get along.” Failing to get along meant you risked anything from an inconvenient job transfer to outright losing that job. When one Army inspector produced an honest report on conditions at the Lockland factory, he was immediately prohibited from entering any Wright plant.

Testimony to the Truman Committee revealed that whenever an Army inspector tried to reject suspect engine material, a Wright exec would insist that the material was “important to the company.” If Wright appealed an inspector’s decision—to the inspector’s supervisor, to an AAF technical advisor, to the Army’s Wright Field itself—the appeal was invariably allowed. Inevitably, Army inspectors came to realize that objections were futile if Wright Aero disagreed.

Wright denied Army inspectors access to the company’s own precision instruments for their inspections, meaning they were limited to purely visual examinations. If they couldn’t see a crack, it didn’t exist. Wright’s excuse was that the Army inspectors weren’t properly trained in the use of the equipment. This was particularly true, the company said, for a device used to test the hardness of the gears in the R-2600’s drivetrain. It became an open secret that Wright was faking the hardness testing of these gears. The military inspectors were also denied the use of rejection stamps or embossing warnings to identify failed parts or engines, since Wright wanted to sell those wares to unsuspecting commercial and export operators.

More than a quarter of the R-2600s built at Lockland failed a basic three-hour test run. Randomly selected engines were also put through a 150-hour quality test, but the Truman Committee found that since 1941 not a single engine had completed the test. One of them failed at 28 hours.

Truman claimed to have personally rejected 400 ready-to-ship Lockland engines. “They were putting defective motors in planes, and the generals couldn’t seem to find anything wrong [with them],” he said. “So we went down, myself and a couple of senators, and we condemned 400 or 500 of those engines. And I sent a couple of generals who had been approving those engines to Leavenworth.” (Fort Leavenworth was the Army stockade in Kansas.)

(HistoryNet Archives)

Wright company inspectors often weren’t the problem. The AAF’s own people too often wanted to go along to get along. Chief Inspector Lt. Col. Frank Greulich tried to intimidate and discredit witnesses who gave negative testimony to the Truman Committee, and Greulich himself lied to the committee a number of times. As one observer put it, “The Committee witnessed the unpleasant spectacle of a lieutenant colonel, a major and several high civilian officials all telling entirely contradictory stories.”

Once the Truman people had finished their investigation, the AAF insisted on repeating their work, inevitably making the same negative findings. But those faults led the AAF to a different conclusion: that the record of engines built at Lockland compared favorably with the record of other types of engines built elsewhere. The best they could say of Curtiss-Wright’s products was that “they were not always the best [but] have been usable.”

One thing became readily apparent. The Lockland scandal was a prime example of what happened when a huge government-built, spare-no-expense factory tried to turn out an enormous quantity of material with inexperienced management and impossible production schedules while maintaining quality in the face of constant changes in tolerances and specifications.

Middle management was so overextended by the sudden wartime demands that a lot of the execs were simply incompetent, the workers inadequately trained and experienced engineers and supervisors too few. The more plants the government built for Curtiss-Wright, the more diluted the cadre of qualified and talented managerial personnel became. Only two percent of the first batch of applicants for jobs at Curtiss-Wright’s new plant in Columbus, Ohio, had any experience in aircraft production, yet they would soon be building Curtiss SB2C Helldivers, which had been described as the most complex single-engine design of its time. The Lockland plant was the biggest single-story industrial facility in the world, but its inept management soon turned the sleek new factory into a cluttered, crowded, ill-lit dump. One AAF report called it “a disgrace to the company and to the Air Forces.”

It was thought at the time, at least by some, that Curtiss-Wright was untouchable because its president, Guy Vaughn, was a big-time player on Capitol Hill. Vaughn was a former automobile racer and speed-record holder who had come up through the ranks at Wright Aero. He was responsible, at least in part, for the development of one of the most important aircraft engines ever built, the Wright J-series Whirlwind. Particularly in its nine-cylinder J-5 form, the Whirlwind was the first reliable, bulletproof aircraft engine available. It was so reliable, in fact, that Charles Lindbergh chose it for his 1927 transatlantic flight, and it never missed a beat. (In truth, though, engineer Charles Lawrance did the heavy lifting and designing for the Whirlwind.)

Vaughn griped that the problems the Truman Committee claimed to be finding were simply “standard and recognized manufacturing and inspection procedures.” During his cross-examination by the committee, Vaughn demanded to know exactly what was wrong with three specific R-2600s that had been crated and ready to ship before being rejected by inspectors. It turned out that one of them lacked a lockwire on a gear, another had corroded cylinders, and the third had a driveshaft gear with a broken tooth and an inoperative magneto—defects that could have led to crashes. Vaughn huffed that he didn’t consider these engines to be defective.

In the end, the Truman Committee toned down its report and Curtiss-Wright ended up suffering no penalty. This despite the fact that the Lockland plant had plainly turned out defective engines with the cooperation of dishonest AAF and company inspectors, and that some of those engines almost certainly went on to kill pilots and crewmen. The Justice Department did sue Wright and eight of its executives for selling the government known defective aircraft and engines, but the suit was never pursued. Three Army Air Force officers, including Greulich, did end up at Leavenworth, however, after being court-martialed for neglect of duty. (Despite Truman’s claim, none of them were generals.)

(National Archives)

The Truman Committee also concluded that Curtiss-Wright had received “far more contracts from the Army and Navy than warranted by the quality of its products or its ability to produce them.” The committee recommended that all Curtiss-Wright contracts be renegotiated, but this never happened either.

However, the committee’s investigation marked the beginning of the end for Curtiss-Wright, a company that had once manufactured and sold more different aircraft, engines, propellers, accessories and parts than anybody else in the industry. Curtiss-Wright had become good at cranking out quantity, but less adept at creating quality. It continued to build second-best P-40s, concentrating on increasing the production rate, lowering costs and maximizing the profit.

By 1947, with war profiteering a distant memory, Curtiss-Wright shut down 16 of its 19 plants. The company’s only possible moneymaking program was an attempt to turn the Curtiss C-46 Commando cargo plane into a pressurized airliner. But C-46s were so cheaply available as surplus that operators were buying and refitting the airplanes themselves. (And none saw the need for pressurization.)

The CW-32 was to be a four-engine airliner with military airlift capability, but the project was canceled in 1948. The company was testing an all-weather jet interceptor, the XP-87, but when an expensive wing modification appeared necessary, the U.S. Air Force insisted that Curtiss pay a major part of the expense. CEO Guy Vaughn refused, and the Air Force retaliated by canceling the project.

After 40 years, Curtiss was out of the airplane business.

Chaos took over the company’s front office as the focus shifted to profit-taking at the expense of R&D. As the excellent book Curtiss-Wright: Greatness and Decline puts it, “A vigorous and well-planned course of action was desperately needed. This, in turn, required a high degree of managerial skill and perhaps a bit of luck. Curtiss-Wright, it seemed, lacked both.” The leadership that took over Curtiss-Wright “came from the world of corporate finance and investment banking,” the book notes, “and had almost no direct connection with, or understanding of, the aviation industry.” By the mid-1950s, Curtiss-Wright “no longer had a distinct identity. The company had no viable product to develop and sell, and overdiversification was dissipating its resources.”

Today the Curtiss-Wright Corporation has its headquarters in North Carolina and manufactures components for aircraft, but the days when the company dominated the U.S. aviation industry ended long ago.

In 1944, Harry Truman became Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate and advanced to the vice presidency after FDR’s reelection to a fourth term. Some say he was chosen to shut him up, others that it was a reward for years of chasing down fraud, waste and abuse in the defense industry. (This part of Truman’s career is detailed in Steve Drummond’s excellent new book The Watchdog: How the Truman Committee Battled Corruption and Helped Win World War Two.) Truman became president only months later, when Roosevelt died suddenly in April 1945.

Marilyn Monroe is perhaps the most unlikely person to have had her life changed by the Curtiss-Wright catastrophe. That’s due to a young American playwright, Arthur Miller, who would later write Death of a Salesman, The Crucible and other classics. But in 1944 he had written a play that flopped after only three performances on Broadway. He decided that if that was the best he could do, he’d take up accounting, or selling insurance. Fortunately, he decided to give playwriting one more try.

(Jack Clarity/New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

In January 1947, Miller’s play All My Sons opened on Broadway, became a huge success and launched his career. Based directly on the Curtiss-Wright scandal, the play told the story of a man who knowingly produced bogus aircraft parts. One batch of his parts—badly cast cylinder heads—resulted in the crashes of 21 P-40s, including one that killed his own son.

In an odd but fascinating mismatch, the now-celebrated Miller fell for actress and sex symbol Marilyn Monroe. Monroe herself sought escape from her dumb-blonde image, and marriage to a successful playwright and intellectual like Miller, she felt, was her ticket to legitimacy. They wed in 1956 but the marriage, like Curtiss-Wright’s dominance of the U.S. aviation industry, soon came to an end.

But for Curtiss-Wright’s fall from grace, it never would have happened.