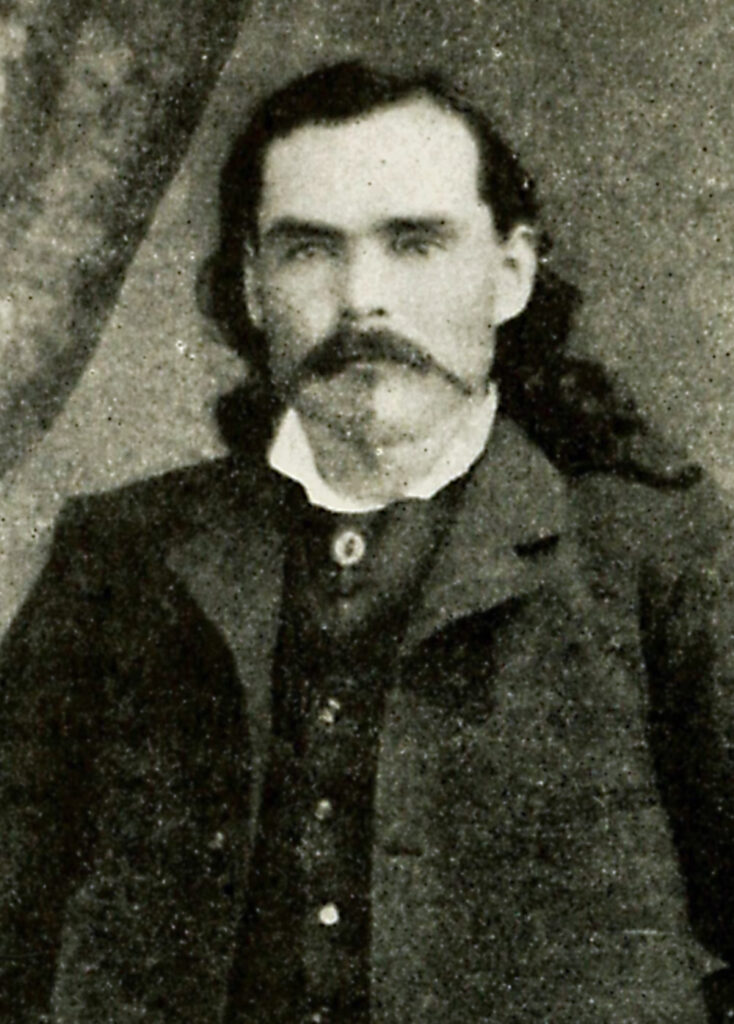

In the end William “Billy” Dixon cared far less about being a legend or hero than he did about the vibrancy of life he had experienced on the Great Plains. Death had flirted with the famed frontier scout and buffalo hunter on more than one occasion, but it was in those harrowing moments he had felt most alive.

A reflective Dixon recalled one of those life-defining episodes in his autobiography, dictated shortly before his death and published in 1914. His mind drifted to his days as a young buffalo hunter at Adobe Walls, a remote outpost of hunters, skinners and tradesmen in the Texas Panhandle. There, in the predawn hours of June 27, 1874, Dixon caught a glimpse of a large body of shadowy objects near a timberline beyond the settlement’s grazing horses. They were moving toward the outpost. Dixon strained his eyes but couldn’t define anything in the murky light. Suddenly, the advancing body “spread out like a fan” and unleashed a collective, thunderous war whoop that “seemed to shake the very air of the early morning.”

Hundreds of mounted Comanche, Kiowa and Southern Cheyenne warriors then burst into view, charging furiously in full regalia. The fearless Comanche Chief Quanah Parker led the pack. Dixon described the scene with vivid, romantic prose—splashes of bright red, vermillion and ochre on the warriors and their horses…scalps dangling from bridles…fluttering plumes of magnificent warbonnets…and the bronzed, half-naked bodies of the riders, glittering with silver and brass ornaments as they emerged from the fires of the rising sun. “There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight,” Dixon confessed. “In after years I was glad that I had seen it.”

Dixon had witnessed one of the last great thrusts by the Plains tribes in defense of their way of life—an ancient, nomadic existence tethered to the once mighty herds of buffalo. By the time of the 1874 Second Battle of Adobe Walls, however, the herds were vanishing at an alarming rate. Dixon, like the buffalo, miraculously survived. He emerged from battle that day as the “hero of Adobe Walls,” having dropped a warrior from his horse with a legendary rifle shot of more than 1,500 yards. In the ensuing decades Dixon became increasingly cognizant of the unique history he had experienced on the Great Plains. Above all he came to appreciate the magnitude those events had had on the development of the American West.

(Rock Island Auction)

“I fear that the conquest of savagery in the Southwest was due more often to love of adventure than to any wish that cities should arise in the desert, or that the highways of civilization should take the place of the trails of the Indian and the buffalo,” Dixon said. “In fact, many of us believed and hoped that the wilderness would remain forever. Life there was to our liking. Its freedom, its dangers, its tax upon our strength and courage, gave zest to living.”

Memories of that life flooded Dixon’s mind. Fortunately, Billy’s greatest champion—his wife, Olive—convinced him to preserve his remembrances for future generations in an as-told-to autobiography. Starting in earnest in the fall of 1912, she faithfully recorded Billy’s running narrative on notebooks scattered throughout their homestead in Cimarron County, Okla. She even kept a notebook in the corral in case her taciturn husband became reflective about the past, ever mindful of his reluctance to fuss over his adventures. Sadly, Billy never read the final manuscript. He caught pneumonia during a winter storm and died shortly afterward at home on March 9, 1913, at age 62. Fellow members of his Masonic lodge buried Billy in the nearest cemetery on Texas soil, in the Panhandle town of Texline.

“Little did we suspect that Death—the enemy from whom he had escaped so many times in the old days—was at hand,” Olive wrote in the preface to his autobiography, “and that the arrow was set to the bow.”

(Library of Congress)

Having inherited her husband’s hefty mantle, Olive faithfully labored over the next 43 years—until her own death—to preserve and promote his legacy. Her love and unwavering dedication to Billy, a man 22 years her senior, is consistently evident in her private letters, published articles, lectures and memorial projects. In the immediate aftermath of his death she dedicated her efforts to publishing his life story. First, Olive enlisted the services of Frederick S. Barde, the “dean of Oklahoma journalism,” to compile Billy’s remembrances into an orderly manuscript originally entitled Life and Adventures of “Billy” Dixon. She then borrowed $500 at 12 percent interest to pay for the printing—a mighty sacrifice for a widow of seven children. Twelve years would pass before Olive finally paid off her banknote, but any hardships proved worthwhile where her husband’s legend was concerned.

Historians and old-timers alike declared the book an instant frontier classic. University of Oklahoma history professor Joseph B. Thoburn, who became one of Olive’s closest friends and confidants, viewed the timing of her work on the book as “almost Providential.” In one letter to Olive he declared, “Posterity will always owe you a debt of gratitude for your persistence in persuading your husband to tell his life story for publication. So much valuable historical material of this class had been lost in the West because the story of a man’s life was permitted to die with him.”

Thoburn spoke truth. If not for Olive’s perseverance, large swaths of Billy’s remarkable life story would never have been recorded. The autobiography alone provided Dixon’s firsthand accounts and context for two of the American West’s most thrilling episodes—the June 27, 1874, Second Battle of Adobe Walls, and the Sept. 12, 1874, Buffalo Wallow Fight.

Buffalo Wallow

At Buffalo Wallow—a sideshow of the Sept. 9–14, 1874, Battle of the Upper Washita River—Dixon, fellow civilian scout Amos Chapman and four enlisted men of the 6th U.S. Cavalry defended a patch of naked ground against a large band of Comanche and Kiowa warriors. For their actions Dixon and the others received the Medal of Honor. Billy’s blunt but gripping narration of the battle to Olive provided the backstory behind the medals.

Dixon described how he and his companions were carrying dispatches from McClellan Creek, in the Panhandle, to Camp Supply in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), some 150 miles to the northwest. They’d been sent by Colonel Nelson A. Miles, then commanding the 5th U.S. Infantry and the 6th Cavalry, whose rations were running dangerously low amid the Red River War, the ongoing campaign to subdue the southern Plains tribes. At sunrise on September 12, their second day out, the small party crested a knoll within plain sight of the Comanches and Kiowas. The warriors quickly encircled the men.

“We were in a trap,” Dixon recalled. “We knew that the best thing to do was to make a stand and fight for our lives.” As the men dismounted, Private George W. Smith gathered the reins of their horses, only to be shot a moment later. He fell face down. At that the horses bolted. A fierce, close-quarters firefight ensued, as Dixon, Chapman, Sergeant Zachariah T. Woodhall and Privates Peter Roth (or Rath) and John Harrington fended off an estimated 125 warriors.

Scanning the open plains for any shelter, Dixon spotted a depression some yards distant where buffalo had pawed and wallowed. As the men sprinted for it under fire, one shot dropped Chapman, who fell with a moan. Roth, Woodhall, Harrington and Dixon kept running till they reached the wallow, then desperately stabbed and clawed at the earth with their knives and hands to throw up a crude earthwork around its perimeter. “We were keenly aware that the only thing to do was to sell our lives as dearly as possible,” Dixon said. “We fired deliberately, taking good aim, and were picking off an Indian at almost every round.”

Chapman and Smith—the latter presumed dead—remained where they had fallen. One of the men cried out for Chapman to make a dash for the wallow, but the scout replied that a bullet had shattered his left knee. Dixon refused to leave Chapman stranded. Despite intense volleys by the enemy, he finally reached his fellow scout, hoisted Chapman on his back and bore the larger man to the safety of the wallow. Chapman later told a dramatically different version of who saved whom that day, a claim the reserved Dixon never contested publicly while alive, much to Olive’s dismay.

(Look and Learn (Bridgeman Images))

Around 3 p.m. merciful fate intervened, as sheets of cold rain provided the defenders with welcome water and pelted their assailants, prompting the Comanches and Kiowas to retreat for warmth and cover out of rifle range. By dawn the next day the warriors had vanished. The break came too late for Smith, who’d been mortally wounded with a punctured lung. In the dark of night Dixon and Roth had manhandled the private back to the wallow, where he died without complaint. Decades later Billy spoke of the cool courage displayed by every man that day and mournfully told his wife that Private Smith still lay buried out on the windswept plains.

Tireless Work

The knowledge that Smith’s grave, as well as the battle site, remained unmarked overwhelmed Olive with a sense of responsibility to honor the memory of Billy and his contemporaries. With that singular mission in mind she leapt from one project to the next. She wrote to magazines and newspapers, often to correct details in published articles about Billy’s life. In 1922 she became a charter member of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society and two years later spearheaded the society’s efforts to mark the 50th anniversary of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls.

On June 27, 1924, more than 3,000 celebrants descended on the remote Adobe Walls battlefield, by then part of the Turkey Track Ranch in Hutchinson County, Texas. They arrived in automobiles, wagons and on horseback, all to pay homage to the memory of a heroic and successful last stand by 28 men and one woman (Hannah Olds, the wife of cook William Olds) against “the flower and perfection” of the Plains tribal warriors.

Andy Johnson of Dodge City, Kan.—one of two living defenders—attended the celebration with a pistol fastened to his waistband. He later regaled the crowd with a stirring account of the battle as airplanes circled overhead. Naturally, Johnson’s story of Dixon’s legendary long shot received prime treatment, though the claim later drew skepticism in some quarters. Olive also made brief remarks, crediting others for the historic occasion. The crowd cheered lustily when a 10-foot-tall monument of the finest Oklahoma red granite was unveiled. Inscribed on it are the names of each Adobe Walls defender.

The successful event only fueled Olive’s commitment to her cause. She had already begun lobbying the society to mark the site of the Buffalo Wallow Fight while simultaneously searching for a publisher to reprint Billy’s book. Despite the book’s critical acclaim a decade earlier, Olive’s hunt for a publisher proved slow and unnerving. In a Dec. 27, 1925, letter to Thoburn, she went so far as to declare that if she couldn’t secure a publisher soon, she would be forced to “sell my land in Cimarron County.”

(Oklahoma Historical Society)

Two years passed before Olive celebrated those two signature achievements—the release of a revised edition of Billy’s autobiography, by Dallas-based P.L. Turner Co., and the placement of a monument at the Buffalo Wallow battleground, 22 miles south of Canadian, Texas. She even successfully lobbied the U.S. War Department to provide a grave marker for Private George Smith.

Still, Olive couldn’t rest. Two years later she made the intensely personal decision to have her husband’s remains reinterred to Adobe Walls. On June 27, 1929—55 years to the day after the storied battle with allied warriors led by Quanah Parker—a police escort led a funeral procession three hours from Texline to the battleground. Reverent spectators lined the route, removing their hats as the caravan passed. A headline in the Amarillo Daily News proclaimed, Col. Billy Dixon Gets Last Wish: Buried at Site of Adobe Walls. Never mind that Dixon had no military rank; he didn’t need one to be remembered.

Immortalized in Print

The model of a devoted widow, Olive ensured her husband’s name would echo through time. She did so tirelessly, lovingly and with humility. Recognizing her immense contributions to the history of the Texas Panhandle, author John McCarty sought her permission to write a biography about her life with Billy, and his vision culminated in the 1955 publication of Adobe Walls Bride: The Story of Billy and Olive Dixon. Initially, Olive had balked at the idea. “Throughout the time when interviews and research were bringing out the story of her life,” McCarty wrote, “Mrs. Dixon steadily maintained that there was nothing distinctive about her or her experiences; she even protested that there would be no interest in a story of her life, as she had done nothing out of the ordinary. All her disclosures were slanted toward one recurring theme: ‘My husband was a great man.’ But she took no credit for Dixon’s achievements.”

Olive died in Amarillo a year later, on March 17, 1956—43 years and eight days after her beloved Billy left this earth. Death stole her swiftly. That evening she had joined daughter Edna and son-in-law Walter Irwin for dinner at a popular barbecue restaurant. On the drive home Olive quietly slumped over on her daughter’s shoulder. She never regained consciousness.

As a child growing up in Virginia, Olive had dreamed of a time when she could “mingle with people who were really doing things in an unusual way.” Stories of the expansive cattle ranches on the Great Plains fueled her imagination, until in 1893, at age 20, she boldly joined brother Archie King in Texas for the adventure of a lifetime. He worked as a cowhand for a Hutchinson County spread, living with wife and child in a crude log-and-sod structure dug out of a bank on Johns Creek some 20 miles from the ranch headquarters. She also visited brother Albert, who wrangled for a neighboring spread.

Olive instantly fell in love with the West, and soon after with one of its icons. Her childhood dream was realized. She’d sought adventure, embraced the pioneer spirit and then married the love of her life. Olive, like her husband, had lived a life worth remembering.

Ron J. Jackson Jr. is an award-winning author from Rocky, Okla., and a regular contributor to Wild West. For further reading he recommends the autobiography Life and Adventures of “Billy” Dixon, as well as Adobe Walls: The History and Archeology of the 1874 Trading Post, by T. Lindsay Baker and Billy R. Harrison; Adobe Walls Bride: The Story of Billy and Olive King Dixon, by John L. McCarty; and Billy and Olive Dixon: The Plainsman and His Lady, by Bill O’Neal.